Three Month Summary

This course has exposed me to the burgeoning field of behavioral economics. Neoclassical economics may be the “study of resource allocation under scarcity,” but behavioral economics is a blend of economics and psychology—the study of how people actually make decisions. Neoclassical models necessarily make simplifying assumptions, and behavioral economics explains the glitches and phenomena that traditional theory excludes. Laboratory experiments in both psychology and economics departments have demonstrated that while the rational consumer is a useful construct, he is ultimately fictitious.

As Clay Shirky shows in Cognitive Surplus, and as Chris Anderson to a lesser degree demonstrates in Free, people often behave in ways that are not profit-maximizing. The traditional foil to neoclassical theory is the ultimatum game: responders will turn down free money if they believe they are receiving an unfair deal. And, as William Poundstone explains in Priceless, decision-making can be influenced by hormones, blood alcohol content, race, gender, and other human variables. Poundstone’s conclusions are not new; economists have been modeling these effects for decades.

What is new is the Internet. Never before has such a market existed, and never before has it been so easily to collect data and study social groups. The Internet is unique in several ways. Firstly, there is virtually no cost to starting an online business—there are zero barriers to entry and exit. Secondly, the Internet allows information to flow phenomenally fast, thereby eliminating information asymmetries. Likewise, it distorts geography and time: individuals across the globe can communicate in real-time, and a researcher can access decades-old news articles with a quick Google search. The Internet is a nearly perfectly competitive market. The prices of goods fall to little more than their costs of production and, at first glance, there seems to be little room for profit.

The Internet’s effect is similar to that of the Industrial Revolution. Today, companies centuries old are failing while start-ups are thriving. The Internet era demands new business models. Michael Porter’s cost-leadership strategy is no longer enough; firms will have to differentiate themselves by adding value for their customers. (One way to do this, Daniel Pink suggests, is by focusing on design and those creative, human touches that cannot be replicated by software.)

The Internet also promotes super-monetary economies. With a glut of entertainment options available, a consumer’s scarcest resources are his or her time and attention. When one’s material needs have been mostly satisfied, he moves up Maslov’s hierarchy of needs. People log onto the Internet to participate, to connect with like-minded individuals. They express themselves in art, writing, and video—they will create for free—in exchange only for an audience. Furthermore, as Clay Shirky points out, people will often take on challenging tasks simply in order to master them or to feel autonomous. On the Internet, success is measured not in dollar signs but in reputation, and the primary currency is that of attribution—giving credit where credit is due.

There are several implications for aspiring managers. Daniel Pink argues that Peter Drucker’s “knowledge worker” has been supplanted by the right- and left-brained “conceptual worker.” While this may be more prediction than perception, it is not unrealistic to suggest that tomorrow’s workers will have to communicate as much as they quantify. The physical workplace is less important than the worker himself; tomorrow’s organizations will be decentralized and office hierarchies will be more fluid. Social media will both unite offices and keep them in touch with the outside world. (For a guide to becoming the ultimate mobile warrior, read Timothy Ferriss’s 4-Hour Workweek; to become a social media expert, read anything by David Meerman Scott.) Finally, in a hyper-connected world, workers will be challenged simply to define their work, to sort out critical information from what is superfluous, and to stay focused. Workers should embrace iterative design theory: “nothing will ever be perfect,” writes David Meerman Scott, suggesting that companies should launch products as soon as possible and revise them later, with user feedback. Managers may need to teach their employees how to work as much as give them orders—a copy of David Allen’s Making It All Work should suffice.

Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (and How to Take Advantage of It) by William Poundstone

Sorry it's been so long, guys.

Priceless is a well-researched history of behavioral economics. Poundstone goes out of his way tell the stories of Sarah Lichenstein, Paul Slovic, S. S. Stevens and the other researchers who punched holes in neoclassical theory—and the result is a book that is thoroughly engaging.

Poundstone argues that prices are largely arbitrary. Just as people are relatively poor judges of absolute temperatures and weights but can easily estimate changes, so too do customers have little sense what goods should be worth. Instead, they judge whether prices are acceptable or not from environmental cues. Poundstone repeatedly demonstrates the power of anchoring: a high set price can pull subsequent estimations of value upward. For instance, amateur and professional real estate agents both conclude a house is worth more when the asking price is higher. Similarly, an overpriced watch in a designer goods store may never sell but serves to justify high prices on other products. And juries award more in damages when lawyers put arbitrarily high prices on their clients’ suffering. (Poundstone opens with an account of the landmark Liebeck v. McDonald’s case, in which a jury awarded Stella Liebeck $2.9 million in damages for the third-degree burns she received when spilled a cup of coffee on herself.)

Poundstone extrapolates the psychology of pricing to discounts in retail stores, menu layouts, and business negotiations. Some tips:

On a menu, center-justify items and list prices without dollar signs.

If an item is on sale, list the new price along with the original. The allure of a bargain may induce customers to spend more than they otherwise would. Instead of raising prices outright, “lower the discount” (232).

When negotiating a business deal with a man, examine his ring finger. If he is unmarried or has a ring finger close in length to his index finger, he is less likely to walk away from a deal.

In behavioral economics, the primary research tool is the classic ultimatum game. Poundstone describes several variations (competitions between genders or races; games played under the influence of oxytocin or alcohol) and their implications. Several experiments reveal biases subjects will not consciously admit to. Poundstone’s book is a powerful study of both pricing theory and modern society.

Free: The Future of a Radical Price by Chris Anderson

Free (Hyperion, 2009) continues the line of thought Chris Anderson developed in The Long Tail. As in his previous book, Anderson approaches digital markets from an economic perspective. While his language isn’t always crystal-clear (don’t read his book before bed), his reasoning is sound and informed.

In the digital era, technological advancement has driven the costs of the inputs of production—primarily bandwidth, processing power, and storage space—down to virtually zero. The challenges this presents are primarily psychological: we need to stop thinking in terms scarcity and start thinking in terms of abundance.

Like Clay Shirky does in Cognitive Surplus, Anderson analyzes nonmonetary economies (but with more statistical data). In the Internet era, the primary currencies are attention and reputation: since consumers have only limited time, producers must compete for it. Twenty-first century business models will focus not on simply delivering a service but adding value for customers (see also Daniel Pink’s A Whole New Mind).

This applies not only to media companies but to manufacturers as well, since even physical goods have some sort of branding or intellectual property associated with them. Anderson examines the Chinese fashion market—where piracy is rampant—to illustrate how designer knock-offs actually drive demand for premium goods. In case study after case study, Anderson proves that free products create markets where there were none.

In his last chapter (pages 251-254) and in various sidebars, Anderson lists over fifty businesses that make money by offering free services. Anderson used to offer a free copy of his book on his website, and any aspiring entrepreneur would do well to read through it. In sum, there are three main business models a company can follow:

Direct Cross-Subsidies: Higher-paying customers subsidize lower-paying ones. Think museum admissions: adults pay while children get in free.

The Three-Party Market: A third party subsidizes the cost of offering customers a product at reduced rates. This is the way the media industry operates: advertisers pay the costs of producing content that anyone can access.

Freemium: Some customers purchase a premium product while others try a basic version at no cost. This is the model most software—think QuickTime (bundled with OSX) versus QuickTime Pro ($29.99)—sells with.

Why do countries have different broadband penetration rates?

Update August 18, 2020: The paper below is a rough draft or working paper. Here is the final paper: Why do countries have different broadband penetration rates? (May 2011).

Broadband penetration is a term I'm using to refer to the proportion of a country's citizens who have access to high-speed broadband Internet services. For my economics research seminar, I'm analyzing the factors that affect broadband penetration at the national. Using a fixed-effect regression, I model broadband penetration against a variety of factors such as GDP and population density. I use data freely available from the World Bank.

This paper is only a rough draft, but I welcome comments and constructive criticism that will help me refine my research. If you know of a paper that would be helpful, please send it along.

Introduction

Today’s markets are global, and both developed and developing countries are increasingly producing service-sector goods. Widespread access to high-speed Internet can be a competitive advantage in today’s knowledge economy (Choudrie and Lee 2004; OECD 2008).

At the same time, broadband infrastructure requires significant investment. Due to economies of scale, the market may be uncompetitive—dominated by a few large firms—and rural or low-income areas may be underserved (Gillett et al 2003; Choudrie and Lee 2004). Since broadband is excludable but largely nonrival—once the infrastructure has been installed in an area, one household’s use does not significantly diminish the service provided to other households—it might be useful to consider broadband as a public good. Governments may want to encourage broadband penetration in order to address equity concerns or modernize their countries.

Gillett et al (2003) suggest that to promote broadband penetration, a government can assume the role of 1) user, 2) rule-maker, 3) financier, and/or 4) infrastructure developer. In the first role, the government stimulates demand; in the latter three, it encourages supply.

In 1999 and 2000, South Korea experimented with several initiatives to encourage broadband penetration (Choudrie and Lee 2004). With programs such as “Cyber Korea 21” and “Ten Million People Internet Education,” the government promoted Internet literacy to stimulate demand. The government also deregulated the telecommunications industry, provided “US$77m of loans [to service providers] at preferential rates,” and prepayed for broadband service to public buildings. The government planned to commit an additional US$926m to extend broadband service to rural areas by 2005. Broadband adoption in South Korea was spurred by the prevalence of Internet cafés that introduced the population to high-speed Internet access and by a highly-competitive telecommunications sector that provided next-generation services at cutthroat rates. South Korea’s high population density also facilitated the spread of the new infrastructure.

The literature suggests that broadband penetration will be influenced by several demand- and supply-side factors.

Demand

Population: Aggregate demand for broadband will be greater among larger populations. One also expects that demand will be greater from more youthful populations.

Wealth: Since broadband is a “premium” service, demand should be greater from wealthier countries.

Education: Gillett et al (2003) argue that “white collar workers . . . are more likely to use advanced communications services.” One expects that broadband penetration will be greater in countries that have more highly-educated populations and that trade primarily in communications and services.

Supply

Telecommunications sector: One expects that supply will be greater in countries with robust telecommunications industries.

Population density: Broadband penetration should be greater in densely-populated countries.

Gillett et al have verified this framework at the level of local municipalities in the United States using data provided by the American Public Power Association (2003), but no study has yet examined broadband penetration rates at the international level.

Empirical Framework

To analyze broadband penetration from time-varying panel data, a linear fixed-effects regression model is used.

where

Y = broadband penetration

X = demand-side variables

Z = supply-side variables

Broadband penetration is measured as the number of fixed broadband Internet subscribers per 100 citizens.

Demand-side variables include the total population as well as the percentage of the population between ages 15 and 64 and the percentage of the population over the age of 64. Since the total population varies widely among the sample data, it has been transformed logarithmically. The collinearity between these three variables is insignificant. One expects all to be positively correlated with broadband penetration.

The latter two variables are included in order to isolate which age group is driving the demand for broadband. One expects that youthful populations will have a greater demand for broadband.

GDP—transformed logarithmically—has been used to measure the wealth of a country. This variable should be positively correlated with broadband penetration. Education should also increase with income levels, and although data on adult and youth literacy rates was available, it would have presented collinearity problems and was not rich enough to be included in the regression. Hence, GDP will be used as a proxy for both the wealth and education levels of a country.

The “white-collar” demand of a country is measured by the logarithmic transformations of commercial service imports and exports (both in U.S. dollars). Countries that trade a high volume of commercial services will likely have a greater demand for high-speed Internet access. The demand of highly-educated citizens is also estimated by the number of researchers and technicians per 1 million citizens. Broadband penetration should be greater in countries that are engaged in more “knowledge work.”

The sole supply-side variable is mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 citizens. Since cellular subscription rates often increase as broadband subscription rates increase (Yang et al 2009), and since broadband providers often also provide cellular service (Yang et al 2009), this variable should indicate the robustness of a country’s telecommunications sector. However, especially in developing countries, high cellular subscription rates may also indicate a lack of fixed-line infrastructure. Even in developed countries (for example, Japan), cellular subscriptions could substitute for fixed-line broadband access and may dampen demand for broadband.

Data

The World Bank freely provides data on the preceding variables for a variety of countries. However, the data was more robust for some countries than others. The dataset excludes countries for which broadband penetration rates were not available for half of the sample period (years 2001 through 2009). Since even fixed effects regressions require variation in order to run, countries for which broadband penetration did not vary from 0 during the sample period were also excluded. Hence, as one might expect, countries that were excluded from the dataset were primarily small, developing nations for which data was not readily available. The final dataset still includes a mix both developing and developed countries. (See the Appendix for a full list. The dataset is also available from the researcher upon request.)

68 countries and 318 observations were included in the sample set.

Results

Figure 1

An F-value of 79.23 and an R2 of 0.74 indicate that this regression is highly significant and explains a large degree of the variation in international broadband penetration rates. Nearly all of the variables, with the exception of GDP and commercial service exports, are as significant.

The parameter total population carries a coefficient of 26.16 and is highly significant, indicating that total population is by far the largest determinant of broadband penetration. Surprisingly, the percentage of the population between ages 15 and 64 significantly decreases broadband penetration, while the percentage of population over the age of 64 increases it by half the amount but is insignificant. These results suggest that while total population drives the demand for broadband, the working age and retiree population of a country does not.

These results could arise from including a disproportionate number of developing countries in the dataset, since in developing countries the working age population may be more likely to be engaged in manufacturing or manual labor—occupations which do not demand high-speed broadband access—rather than knowledge work. Since the number of researchers and technicians in a country do significantly drive demand (albeit only slightly), this conclusion seems valid.

The wealth and education of a country, as measured by the logarithmic transformation of GDP, would decrease the demand for broadband were it significant. Income distribution rather than total wealth may be a more important driver of broadband demand, since broadband (as a premium communication service) is more likely to be demanded by the upper classes. This is supported by the results of the regression in Figure 2. With an F-value of 133.62 and an R2 of 0.83, this regression is actually more significant (but less telling) than the one in Figure 1. In the regression in Figure 2, GDP per capita increases broadband penetration only slightly but is highly significant.

After total population, the second-largest determinant of broadband penetration appears to be a country’s commercial service imports. While commercial service exports also positively influences broadband penetration, this parameter is insignificant. These results indicate that countries heavily trading in services will have greater broadband penetration rates. Only commercial service imports could drive broadband demand if wealthier countries are importing services from developing ones, e.g., if developed nations like the United States are outsourcing programming or accounting jobs to developing countries like China and India.

Mobile cellular subscriptions also influence broadband penetration, albeit only slightly. This suggests that a robust telecommunications sector is integral to widespread broadband penetration. Because mobile cellular subscriptions appear to increase broadband penetration, there is no significant trade-off between cellular subscriptions and broadband subscriptions. Instead, the two may be complements.

Figure 2

I plan to run a similar regression using only OECD countries.

Conclusions

At the international level, demand-side variables determine broadband penetration more than supply-side variables. The largest determinant of demand is total population, which is largely outside a government’s control. From a policy perspective, governments can best encourage broadband penetration by stimulating the telecommunications and service sectors of their economies. Service-sector industries drive the demand for broadband and provide a healthy market for premium, twenty-first century telecommunications services.

Literature Review

Sharon E. Gillett, William H. Lehr, and Carlos Osorio, “Local Government Broadband Initiatives,” 2003 [pdf].

Jyoti Choudrie and Anastasia Papazafeiropoulou, “Lessons learnt from the broadband diffusion in South Korea and the UK: Implications for future government intervention in technology diffusion,” 2006 [pdf].

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “The Future of the Internet Economy,” 2008 [pdf].

Heedong Yang, Youngjin Yoo, Kalle Lyytinen, and Joon-Ho Ahn, “Diffusion of Broadband Mobile Services in Korea: The Role of Standards and Its Impact on Diffusion of Complex Technology System,” 2009 [download pdf].

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Professor Ron Cheung for generously guiding my research.

Appendix

The full list of countries in the dataset is as follows: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Armenia, Aruba, Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belarus, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Bermuda, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Cape Verde, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Congo, (Democratic Republic), Costa Rica, Cote d'Ivoire, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Faeroe Islands, Fiji, Finland, France, French Polynesia, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Greenland, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hong Kong SAR, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Korea (Republic of), Kuwait, Kyrgyz Republic, Lao PDR, Latvia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Libya, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, China, Macedonia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Micronesia, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Netherlands, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Northern Mariana Islands, Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Palau, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, Samoa, San Marino, Sao Tome and Principe, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Sudan, Suriname, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Syrian Arab Republic, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, Virgin Islands (U.S.), West Bank and Gaza, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

FastCo interview with Marcus Buckingham, author of First, Break All the Rules

Every manager is different, but what they do differently you could sum up with that mantra I put in chapter two, "They don't try to put in what God left out; they try to draw out what God left in. That's hard enough."

Great interview over on Fast Company with author Marcus Buckingham, of First, Break All the Rules fame. I love his data-driven approach to analyzing business leadership.

Cognitive Surplus by Clay Shirky

Cognitive Surplus (Penguin Press, 2010) is a sequel of sorts to Shirky’s popular 2008 book Here Comes Everybody. Shirky writes on his website that he “stud[ies] the effects of the Internet on society,” and both titles examine group dynamics on websites like Wikipedia, MySpace, and Twitter. In Cognitive Surplus, Shirky argues for the potential of collaborative new media to organize people to have a positive impact on society, and he supports his theories with examples of charitable organizations, social justice initiatives, and open-source software. Shirky is a professor of new media and journalism at NYU, and, though his arguments lack empirical rigor, his case studies are persuasive.

Shirky argues that forty-hour workweeks and rising prosperity have given us a “cognitive surplus”—that is, excess free time we used to otherwise spend watching television (Chapter 1). Since the Internet has democratized to the tools of media production, passive consumers have switched into active participants.

Using landmark psychology studies and behavioral economics, Shirky builds the case that people will often create for nonmonetary reasons. To the editors of Wikipedia or the teenage girls behind Grobanites for Charity, more important than monetary compensation are shared values and engagement in a community. Shirky also points out that individuals will often take on challenging tasks in order to master them or feel autonomous. Shirky’s hopeful thesis, quite simply, is that the Internet fosters collaboration that can use our free time for social good.

Shirky analyzes how fans of the South Korean boy-band Dong Bang Shin Ki organized to overturn trade legislation; how Nisha Susan’s Facebook group, the Association of Pub-going, Loose and Forward Women, changed women’s rights in India; and how open-source software like Linux and Apache get produced. Most relevant to business readers is his last chapter, where he offers a set of guidelines for fostering digital collaboration:

Start small: “Projects that will work only if they grow large generally won’t grow large” (194).

Ask “Why?”: “Designers have to put themselves in the user’s position and take a skeptical look at what the user gets out of participating, especially when the motivation of the designers differs from that of the user” (195).

Behavior Follows Opportunity: “What matters is how [users] react to the opportunities you give them” (196).

Default to Social: “The careful use of defaults can shape how users behave . . . . By assuming that users would be happy to create something of value for each other, Delicious [a social bookmarking site] grew quickly” (197).

A Hundred Users Are Harder Than a Dozen and Harder Than a Thousand: “A small group where everyone knows everyone else can rely on personality to arrange its affairs, while a large group will have some kind of preexisting culture that new users adopt. In the transition between those two stages is where culture gets established” (198).

People Differ. More People Differ More: “In participatory systems, . . . the behaviors of the most active and least active members diverge sharply as the population grows . . . . [Developers] can take advantage of this divergence by offering different levels of involvement” (200).

Intimacy Doesn’t Scale: “Yahoo.com host millions of mailing lists, to which tens of millions of people subscribe, but people are either on a mailing list or they are not—the lines around the individual clusters are clearly drawn. . . . [The] allegiance [of those users] is to the local cluster of people on their mailing list” (201).

Support a Supportive Culture: The riders in an Amtrak quiet car are “willing to police the rules themselves, because they know that if an argument ensues, the conductor will appear and take over enforcement” (202).

The Faster You Learn, the Sooner You’ll Be Able to Adapt: “When . . . Flickr.com was experimenting most actively with new features, it sometimes upgraded its software every half hour . . . . Meetup.com . . . has its designers watch people trying to user their service every day, instead of having focus groups every six months. . . . [S]uccessful uses of cognitive surplus figure out how to change the opportunities on offer, rather than worrying about how to change the users” (203-204).

Success Causes More Problems Than Failure: “As a general rule, it is more important to try something new, and work on the problems as they arise, than to figure out a way to do something new without having any problems.”

Clarity is Violence: “Culture can’t be created by fiat. . . . [T]he task isn’t just to get something done, it’s to create an environment in which people want to do it. [Allow groups] to accrue more governance as they grow” (205).

Try Anything. Try Everything: It is impossible to predict what will be successful, so try everything and allow users to experiment (“the only group that can try everything is everybody” (207)).

4 Ways the Web is Changing Communications

The web is changing how we organize information in four ways:

Taxonomies (think the Dewey Decimal System or biological classification) used to be necessary to organize information, but the web recognizes that categories are often fluid. Would my hypertext novella be found in the nonfiction, new media, prose or poetry section of a bookstore? The answer is neither and all four—it depends on who is looking for the book. With hyperlinks and tags, the web's architecture is primarily relational.

We rarely enter websites via their splash pages and instead access the page we want via Google, Bing, or another search engine. Even though technology allows news to break faster and memes to spread virally, old information is not so much forgotten as pushed to the fringes. For instance, Google "Ryan Gosling" and three of the top six hits will be images from The Notebook, even though the movie is seven years old and Gosling has starred in a movie every year since (including 2010's Blue Valentine, which won two awards and was nominated for seventeen more). Since old information can be accessed as easily as new, the web is inherently nonlinear.

With a blockbuster movie, a prime-time television show, or even a print book, the dialogue is one-way—from artist to audience. But the web has given consumers a voice and it rewards them for using it. If web content does not facilitate audience participation, surfers will take their attention elsewhere. The web is by nature interactive.

Literary writing is largely absent from the web because designers have not yet found ways to humanistically display longer works. The scroll bar on the side of a browser window actually represents a technological regression (think Egyptian papyrus scrolls). Longer documents, unless intuitively organized, lose all the advantages of print books (the abilities to instantly jump from beginning to end and to see how far you have progressed in the text). Because screen reading can be somewhat uncomfortable, web writing tends to be digestible in shorter chunks (e.g., the length of a blog post).

For my creative writing senior project, I'm writing a prose-poetry hypertext novella—a book-length work organized as a website. My novella tries to takes advantage of the above properties. It's partly an homage to my pre-digital childhood and partly a collage of memories (our present encompasses our past). Think of it as a fictional Wikipedia or a digital choose-your-own-adventure—it's an experiment in nonlinear storytelling.

I'm hoping these guys will publish it.

The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More by Chris Anderson

In comparison to David Meerman Scott's Real-Time Marketing & PR, Anderson's The Long Tail offers a rather sophisticated economic analysis of how the Internet is changing business. Anderson focuses mostly on the media and entertainment industries (probably because of his background as editor-in-chief of Wired), but he does do a superb job of extending his analysis to traditional retail (by examining Amazon.com and eBay). Anderson's research is a bit outdated—most of his data comes from before 2006, when the first edition of his book was published—but his theories are still relevant five years later. In 2008 he published an expanded second edition with an additional chapter on "The Long Tail of Marketing."

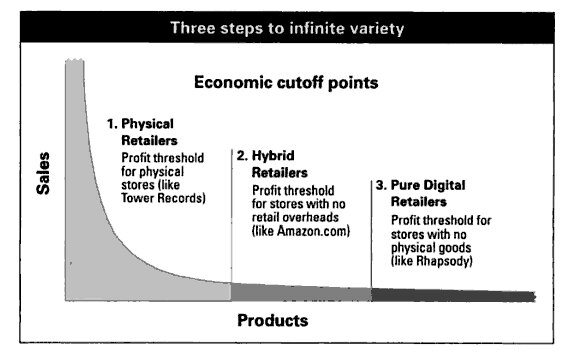

Anderson argues that the Internet is lowering the traditional costs of retail. In the past, companies were forced to offer only "hits" that had mass appeal. The world of physical products is inherently limited and there are opportunity costs to carrying on product over another. A movie has to earn enough at the box office to justify giving it screen time; a television program has to attract enough of an audience justify its spot in prime-time; and a CD has to earn shelf space by selling more copies than a less-popular album.

But, online, companies can offer infinite variety with little-to-no distribution costs. Services like Rhapsody.com or Netflix can offer thousands of mp3s or movie titles and deliver them to the consumer for the price of a broadband connection. Listing another product only costs (ever-cheaper) space on a server. Media companies can tap "the long tail" of the demand curve:

(The Long Tail 92)

The curve extends asymptotically: as Rhapsody added more mp3s to its library, it found that every single one of them sold.

Anderson's insight is that, in aggregate, these niche products can comprise a significant market. By examining companies from KitchenAid to LEGO—which have both physical and digital store fronts—he finds that online sales are becoming an increasingly large portion of revenue and profits.

(The Long Tail 132)

Because enthusiasts are often willing to pay more for niche products, the margins on them can be higher.

There are several implications of this long-tail shift. The first is that, as any microeconomist will tell you (and Anderson worked with Hal Varian, author of my microeconomics textbook), greater choice unambiguously increases welfare: consumers can find precisely the product they want at the price they are willing to pay. Secondly, consumers have more power than ever before because they can voice their opinions via blogs or product reviews ("twist[ing] some arms" with marketing “can only do so much" (232-233)). Ultimately, Anderson foresees mass culture fragmenting into tightly-knit, globe-spanning niches.

The challenge is to help consumers navigate this sea of variety. Long-tail businesses can crowdsource production and increase variety by aggregating the inventories of thousands of sellers (think Amazon Marketplace or eBay), but Anderson suggests that they can also play a (third) role as filters. With smart recommendation software (think Pandora's music genome project), retailers can lead consumers to new products they are likely to buy.

Finally, Anderson does an excellent job of placing the long-tail shift in historical context by examining the distribution innovations by Sears, Roebuck, and Co. and the cultural transformation caused by the home VCR.

Real-Time Marketing & PR by David Meerman Scott

With his 2008 bestseller The New Rules of Marketing & PR, David Meerman Scott redefined contemporary marketing thought. Scott explained how existing advertising strategies—expensive campaigns and interrupting television commercials—had been replaced by search engine optimization and websites that engage customers when they are actively seeking information about a product. In Real-Time Marketing & PR, Scott expands upon that line of thought by emphasizing the value of using new media tools to engage customers constantly and in real-time. Real-Time is more of a practical guide than a book of theory; Scott’s writing is characteristically informal, and his book is likely a compilation of posts from his popular blog Web Ink Now. Scott has a significant social media following and frequently speaks at corporate events.

In Real-Time Marketing & PR, Scott’s thesis comes (ironically) in the last chapter:

The explosion of online communication has led to a . . . loss of vendor control . . . in recent years. With email, social media, and alternative online media, consumers suddenly regained their collective voice in the marketplace. Faced with a vendor’s offer, consumers can once again scoff, rave, critique, or compare—and be heard far and wide. . . .

Far from making everything “new,” as many pundits insist, the Web has actually brought communication back full circle to where we were a century ago. What people respond to, and the way they make purchase decisions, really hasn’t changed at all. The difference is that word of mouth has regained its historic power.

The Web is just like a huge town square, with blogs, forums, and social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook serving as the pubs, private clubs, and community gathering places. People communicate online, meet new people, share ideas, and trade information. And yes, they sell products, too. (199)

Scott illustrates the power of social media through several poignant examples. In the most telling, Dave Carroll, a relatively-unknown rock musician from Canada, takes down United Airlines via a catchy song on YouTube. When baggage handlers mistreat his beloved Taylor guitar, Carroll seeks recompense by contacting the company through traditional channels. But after being shunted between customer service outlets for months, he writes the song “United Breaks Guitars” and posts it to YouTube. The video gains thousands of views within a day and over two million within a week; when CNN, Fox News, CBS, and even the BBC pick up the story, Carroll becomes a mass-media sensation. United continues to ignore the issue, but nimble companies like Calton Cases and Taylor Guitars reach out to Carroll to collaborate. While United suffers significant brand damage—their formal apology is only belated—both Taylor and Carlton see their sales skyrocket. “When luck turns your way, you can’t squander it,” says Bob Taylor of Taylor guitars. “This was a big branding leap.” Three months after his video, Carroll continues to speak to airlines and even the Senate about consumer rights. The lesson? Companies cannot afford to ignore the conversation occurring about them in real-time. [Read the full case study in the first chapter of Scott's book (pdf).]

“An immensely powerful competitive advantage flows to organizations” that are the first to break or act on a news story (35), and in the always-on new media world, even waiting “a whole hour” may be too long (36). Constantly monitoring Internet traffic sounds time-consuming, but Scott does offer some tips, including a detailed job description for a “chief real-time communications officer” (176) and some guidelines for freeing employees to use social media (and influence the conversation about their company in real-time) (162). Since the pace of business has increased, companies need to supplement their existing marketing programs with live communication strategies. In the end, “real-time is a mindset” (210).

Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors by Michael E. Porter

Michael Porter's Competitive Strategy was originally published in 1980 and has since become a classic of MBA programs and graduate economics courses in game theory. Porter’s book reads like a textbook—each chapter begins with a paragraph introduction but then follows with an outline of the relevant ideas, Porter is careful to exhaust all possibilities. Porter supports his theories with examples from the manufacturing sector. His micro case studies range from industries like construction machinery (Caterpillar and John Deere); to American car manufacturing (GM and Ford); “minicomputers” (Hewlett-Packard and Texas Instruments); and consumer watches (Timex and Swiss manufacturers). While Porter’s examples are a bit dated (he discusses “recent” legislation from before 1980), and while he admits in the updated introduction that “more service examples could be added” (xiii), he very thoroughly presents a framework for analyzing competition in any industry.

Porter posits the existence of five competitive forces within an industry:

Threat of Entry: “The threat of entry into an industry depends on the barriers to entry that are present, coupled with the reaction from existing competitors that the entrant can expect” (7).

Intensity of Rivalry among Existing Competitors: “Rivalry among existing competitors takes the familiar form of jockeying for position—using tactics like price competition, advertising battles, product introductions, and increased customer service or warranties” (17).

Pressure from Substitute Products: “All firms in an industry are competing, in a broad sense, with industries producing substitute products” (23); the threat of substitute products comes from outside the industry.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: “Buyers compete with the industry by forcing down prices, bargaining for higher quality or more services, and playing competitors against each other” (24).

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: “Suppliers can exert bargaining power over participants in an industry by threatening to raise prices or reduce the quality of purchased goods” (27).

In Porter’s view, competition plays out like a game of chess; he discusses “Competitive Warfare” in terms of “offensive or defensive moves” (89), and he frequently refers to the “battle” (189). Firms have three generic strategies that they can take:

Overall cost leadership: “Low cost relative to competitors becomes the theme running through the entire strategy” (35). This is a strong position to hold because it “protects the firm against all five competitive forces” (36) (“bargaining can only continue to erode profits until those of the next most efficient competitor are eliminated” (36)).

Differentiation: “Approaches to differentiating can take many forms: design or brand image . . . , technology . . . , features . . . , customer service . . . , dealer network . . . , or other dimensions” (37). Differentiation courts customers with “lower sensitivity to price” (37) and it “avoids the need for a low-cost position” (38).

Focus: “The final generic strategy is focusing on a particular buyer group, segment of the product line, or geographic market” (38). The firm following the focus strategy may strive for cost leadership, differentiation, or both, but only for “its narrow market target” (39).

Porter then offers a sophisticated framework for analyzing competitors and inferring their strategic standings (Chapters 3 and 7). Firms communicate their “pleasure or displeasure” as well as information about themselves through a variety of market signals (Chapter 4) (89). Porter discusses industry evolution and how the five competitive forces play out during different stages of “the product life cycle” (Chapter 8) (158). He follows with a detailed Part II that analyzes and recommends strategies to follow in fragmented, highly-competitive industries (Chapter 9); emerging industries in which a new product has just been introduced (Chapter 10); mature industries (Chapter 11); and declining industries (Chapter 12). He concludes by analyzing globalization in Chapter 13.

A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future by Daniel H. Pink

Is the MFA the new MBA?

Daniel H. Pink argues that today’s knowledge workers must augment their logical and analytical abilities with conceptual and creative skills. Pink identifies a “high-concept, high-touch” world and then delineates six key traits knowledge workers should cultivate. Pink supports his assertions with a flurry of statistics, factoids, and case studies: A Whole New Mind is more of a popular science book than a college textbook. But it is a quick, engaging read, and at the end of every chapter, Pink offers a “Portfolio” with advice for developing each of the six traits.

Delving into some soft psychology, Pink begins by defining L-directed and R-directed thinking:

Some people seem more comfortable with logical, sequential, computer-like reasoning. They tend to become lawyers, accountants, and engineers. Other people are more comfortable with holistic, intuitive, and nonlinear reasoning. They tend to become inventors, entertainers, and counselors . . . .

Call the first approach L-Directed Thinking. It is a form of thinking . . . that is characteristic of the left hemisphere of the brain—sequential, literal, functional, textual, and analytic. [It is] ascendant in the Information Age [and] exemplified by computer programmers . . . . Call the other approach R-Directed Thinking. It is a form of thinking . . . that is characteristic of the right hemisphere of the brain—simultaneous, metaphorical, aesthetic, contextual, and synthetic. [It is] underemphasized in the Information Age [and] exemplified by creators and caregivers . . . . (26)

Pink’s thesis is not that R-Directed thinking is superior to L-Directed, but that modern workers need to utilize both attitudes in order to thrive.

Pink argues that we have actually surpassed Drucker’s Information Age and entered the “Conceptual Age.” Pink identifies three forces at work: Asia, Automation, and Abundance. The first two are threats to today’s knowledge workers. Programmers in China and accountants in India can perform the same tasks as white-collar workers in the U.S., but for much less money (which allows them to earn a comparatively upper-middle class lifestyle overseas). Secondly, as computers become more sophisticated, L-Directed tasks will increasingly become automated. Consumers can go online to file their taxes, download divorce contracts, or obtain basic medical diagnoses; accountants, lawyers, and doctors who only fill out paperwork will become obsolete. And, finally, in our age of material abundance, products must do more than compete on the level of utility.

The typical person uses a toaster at most 15 minutes per day. The remaining 1,425 minutes of the day, the toaster is on display. In other words, 1 percent of the toaster’s time is devoted to utility, while 99 percent is devoted to significance. (80)

Products must appeal to customers’ aesthetic sensibilities in order to stand out.

Pink’s six traits are Design, Story, Empathy, Symphony, Play and Meaning. The first four refer to communication skills. Well-designed products are easy for humans to use (the 2004 Palm Beach ballots illustrate the perils of poor design). Stories weave disparate facts into a memorable whole; likewise, symphony is the ability to connect seemingly unrelated information and to think holistically. Finally, empathetic workers yield higher results (doctors who build relationships with their patients achieve higher rates of recovery, and this ability is more important than IQ, performance in medical school, hospital funding, or any other measure). Play and Meaning are ways to make the workplace more engaging.

On the whole, these are traits that cannot be replicated by computers and tend to become lost in long-distance telecommunication. These six senses add a human component to a service. Pink predicts that they will still be in demand in the immediate future.

The Definitive Drucker by Elizabeth Haas Edersheim

Peter Drucker is a business legend. He has contributed more to management theory than any other thinker, and he has inspired, mentored, and consulted with the CEOs of the world’s most successful companies. In 2005, at the age of 94, he invited Elizabeth Haas Edersheim to have unprecedented access to his person. For sixteen months, and for four to eight hours every day, Edersheim interviewed Drucker with the ultimate goal of creating a biography of his ideas. The result is The Definitive Drucker, which is both a primer of Drucker’s main ideas and a catalogue of personal quotes and wisdom. Edersheim supports Drucker’s theories with case studies and interviews (surprisingly in-depth), and she directs the book at “tomorrow’s executives” (every chapter heading is a question to provoke self-analysis and reflection).

Drucker coined the term “knowledge worker.” He is responsible for identifying the shift in the late 1980s from an industrial, manufacturing-oriented business landscape to a modern “Lego World” in which (1) information flies at hyperspeed; (2) companies have never-before-seen geographic reach; (3) customers defy demographic assumptions; (4) customers have increasing control of companies; (5) and the boundaries within and between companies are blurry and fluid.

Drucker repeatedly emphasized the value of knowing and connecting with customers. Companies need to continually ask themselves: Who are my customers, and what are their needs? The relationship between customer and company is increasingly complex, and Edersheim’s case study of Proctor & Gamble reveals that the company became successful only after focusing not on retailers (who valued simple product lines and timely delivery) but on consumers (whose needs were personal).

Drucker’s prescription for innovation echoes (or, rather, inspired) Timothy Ferriss. Drucker’s advice is to be aggressive where you lead but abandon profitable ventures. Edersheim offers the example of General Electric, which began as an industrial manufacturer but is increasingly involved in financial services and media. Innovators do more than tweak existing products: like Steve Jobs and Apple, they anticipate demands and create new markets.

Drucker’s most lasting contribution is his insight into managing and retaining knowledge workers. Because knowledge is intangible and fluid, employees who feel unfulfilled can easily take their skills to another company. Workers who are invested in and engaged in their work are more productive (organizations like Electrolux use online message boards to allow employees to “bid” for projects). It also helps if employees feel like they are part of a special team (Bob Taylor demonstrated the power of this culture at the famous the Palo Alto Research Center, where the modern personal computer was born). Drucker and Edersheim believe that the companies of tomorrow will be flat and decentralized. Management’s role will be to coordinate and unite disparate teams.

The 4-Hour Workweek by Timothy Ferriss

The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich is primarily a lifestyle guide. Ferriss may minutely detail how to automate revenue streams—he flowcharts the process and recommends specific companies to contact—but primarily he teaches an attitude that could be described as a mix of confidence and entitlement. This is how he recommends a “NR” or “New Rich” respond to a difficult customer:

Customer: What the &#@$? I ordered two cases and they arrived two days late?

Any NR—in this case, me: I will kill you. Be afraid, be very afraid.

(I have also seen Ferriss interviewed by Neil Strauss, author of The Game: Undercover in the Secret Society of Pick-up Artists. The attitude Ferriss recommends for the “NR” resembles Strauss’s vision of the Pick-up Artist (“PUA”). The 4-Hour Workweek applies Game social dynamics to office life.) Ferriss will recommend getting away with whatever you can—“What gets measured gets managed,” he says, quoting Peter Drucker—and working not efficiently but effectively.

In other words, work smarter. If “80% of the outputs come from 20% of the inputs” (Pareto’s famous Law), it is neither necessary nor ideal to spend resources getting outputs to 100%. One’s goal should be simply to tip the 80/20 ratio as high possible. If 90% of sales come from interactions with 10% of customers, then time is being used effectively. Ferriss advocates aggressive prioritization: “Focus on the important few [tasks] and ignore the rest.” He never reads the news.

Ferriss also explains how to start up a quick online retail business. He walks the reader through conceiving a product, testing it before production, advertising on the web and in print, and finally setting up automatic customer service and shipping procedures. Ferriss went through the process with his company, BrainQUICKEN, LLC, and he is able to recommend specific services and websites.

Ferriss is this thorough throughout his entire book. At times he may champion the free market to an almost radical extent—are there be ethical considerations in using Indian data miners to read email?—but his advice is specific enough to be applied by entrepreneurs and office dwellers alike (I plan to recommend it to Richard Nash, my mentor and the CEO of start-up Cursor and Red Lemonade). Ferriss’s aims to streamline personal and professional life, and he is right to point out that in a information-era economy, the most important resources are time and mobility.

Making It All Work by David Allen

David Allen could rightfully be called a personal productivity guru. His 2002 bestseller Getting Things Done inaugurated a movement that spread amongst writers, bloggers, and techies. Luminaries brag about being “GTD blackbelts.” Allen reports that each day fifty new blog posts are written about GTD, and there has been a raft of software tools developed (and marketed) to help users implement his process.

In Allen’s world, mastering workflow allows the individual to achieve a zen-like state of focus. Allen theorizes that the mind operates like computer RAM and will freeze up if it has too many open loops running at once. The solution, though, is not to decrease your commitments but rather to capture and sort them all. If your tasks are organized in a system you can trust to remind you of them—well, then you can stop thinking about everything you need to do and just do it.

Allen suggests that his process should be applied both in the office and at home. (Thus the subtitle, Winning at the Game of Work and the Business of Life.) The only way to fully de-stress is to capture all of your open loops.

Making It All Work teaches the reader a thinking process without worrying about the specific tools he uses. Allen’s solution is not the latest tool or gadget hyped to “boost productivity,” but rather a fundamental way to grapple with the variety of inputs in a knowledge-era economy.

The Processing Flowchart

How to get information out of your head and into a GTD system:

Capture—Write down everything on your mind, regardless of whether it’s a project, a to-do, a personal goal such as “get fit,” or something large and ambiguous like “Mom."

Clarify—Is it actionable? If so, ask yourself:

What’s the desired outcome?

What’s the next action?

Organize—Sort the action depending upon what it is:

Actions, if they don’t have specific due dates, go into context-sorted lists. If they do have specific due dates or you don’t need to worry about them until certain dates, write them down on your calendar.

Outcomes are larger goals. Keep track of them on lists sorted by horizon.

Incubating items are items you’re not sure what to do with yet. Write them on a Someday/Maybe list—to be reviewed weekly—or write them on your calendar.

Support or reference material goes into project-specific, labeled files folders or notebooks. For general thoughts, keep a journal.

Reflect—Review all of your projects weekly. Information changes over time. Items that were important before may no longer be priorities, or you may need to take different next steps to keep your projects moving. If you don’t review your lists, you won’t keep them current and you won’t trust your system. And, as David Allen says, “you can only feel good about what you’re not doing when you know what you’re not doing.” Reviewing gives you a sense of perspective.

Engage—With your lists you can objectively evaluate all of the possible next actions you can take. To remain productive, choose actions that most align with your values (Strategy) and that you can complete with the time, energy, and materials you have available (Limiting Factors).

Organizing on the Road Map (p. 136)

Incorporating All of the Engagement Factors (p. 179)