Termites in the Trading System by Jagdish Bhagwati

Preferential trade agreements (PTAs) undermine the global trading system. They divert trade away from efficient nonmember countries; impose costs on private enterprise; and take advantage of smaller nations.

Firstly, PTAs “divert trade from the cost-efficient nonmember countries to the relatively inefficient member countries” (49). The logic is simple: there are probably countries outside of the PTA that can produce at least some of the traded goods more efficiently than the PTA members can. In addition, PTAs lock countries into being trading partners. “In today’s world of volatile, kaleidoscopic comparative advantage” (60), a PTA member may lose their comparative advantage or a PTA nonmember may develop a significant comparative advantage over the PTA members. PTAs divert trade away from the most efficient allocation.

Secondly, the PTA “spaghetti bowl” is a drain on private enterprise (60). Businesses must expend significant resources “to discover the optimal sourcing” of components (69). The work is “particularly onerous for small enterprises” and “appallingly difficult for the poorer countries” (70). A 2005 Financial Times editorial elaborated:

Bilateralism distorts the flow of goods, throws up barriers, creates friction, reduces flexibility and raises prices. . . . While larger companies have a hard time keeping track, for small groups it is impossible. Bilateral agreements cause the business community to work below its potential. . . . If left unchecked, their continued growth has the potential to hinder the development of the global production system. (70)

Thirdly, the hegemonic powers use PTAs to take advantage of smaller nations. The US and EU frequently use their negotiating power to insert “‘values-related’ demands” into PTAs (74). These stipulations usually have to do with environmental or labor standards. Why is this bad? “Generally speaking, countries will have different sequences by which they approach different dimensions of labor standards” and environmental regulations (76). The values-related demands would be unlikely to be agreed to in multilateral negotiations; PTAs are “a strategy of ‘divide and conquer’” (81). Moreover, these demands are usually the product of domestic lobbying efforts (such as from the AFL-CIO) rather than altruistic intentions.

PTAs divert trade away from efficient nonmember countries; impose costs on the business community; and take advantage of smaller nations. PTAs undermine the global trading system.

Origins of the Pax Britannica and the Pax Americana

Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium by Ronald Findlay and Kevin H. O’Rourke vs. Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy by Douglas A. Irwin

tldr:

Britain and America’s ascensions to hegemony illustrate the virtuous cycles of “power and plenty” (Findlay and O’Rourke xix). The Pax Britannica (1815–1914) and the Pax Americana (1945–present) were characterized by relative peace and relatively free trade between large parts of the world. This paper will focus the conditions that gave rise to each superpower’s dominance. British and American foreign policies shared some similarities: both countries created large free trade zones and both spent heavily on their militaries. They also both benefited from fortunate geographic locations. However, the motivations and economic policies of the two countries were diametrically opposed. The result, perhaps, was that global growth patterns differed significantly during these two periods. Regardless of the differences, though, wealth led to geopolitical power and geopolitical power brought further wealth—a virtuous cycle.

Full Summary

Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy by Dani Rodrik

Book Summary

Globalization must respect national autonomy. Globalization has failed to “deliver effective economic policies for growth and inclusion” (263) and it “has not lifted all boats” as its champions promised that it would (2). In light of this, the nationalist and populist backlash against globalization should not be surprising. Globalists assumed that globalization would bring widespread benefits, but the conventional wisdom on globalization was wrong. Economists bear some responsibility for this: they oversimplified models during public debates. Leaders should not respond to the backlash against globalization with protectionism. Rather, they should support policies that balance the need for international cooperation with greater respect for national sovereignty.

The conventional wisdom on globalization is wrong.

Countries can grow without liberalizing. China—the clearest counterfactual—has grown by pursuing “a variety of policies that violate current trade rules” (3). Rodrick also authored a 2005 study that found that “fewer than 15 percent of significant economic liberalizations produced growth accelerations, and only 16 percent of growth accelerations were preceded by economic liberalization” (55-6).

Free trade has losers—namely, low-skilled domestic workers. Standard economic theories on comparative advantage suggest that “trade agreements do not create jobs; they simply reallocate them across industries” (211)—often to other countries. Meanwhile, the “big winners” under globalization have so far been “financiers and skilled professionals” (2). Globalization has thus been a “key contributor” to rising inequality in developed nations (2).

Globalization has not deepened global integration. Today, national allegiances are stronger than both global or even local ties (21). Brexit and the Greek financial crisis also show that the European Union—an “unprecedented experiment” in multinational cooperation (46)—remains fractured, despite decades of economic integration. National sovereignty continues to remain important in this era of “hyperglobalization” (4).

Globalization does not necessarily spread Western values. Russia, Hungary, and Turkey, for example, are “illiberal democracies” (172): they hold elections, but their elections are neither free nor fair and their citizens (especially minorities) lack fundamental civil rights. Countries can be democratic without be liberal.

Manufacturing might not be a reliable and “rapid escalator to higher income levels” any longer (153). As manufacturing becomes more automated, the sector will demand high-skilled rather than low-skilled labor and developing countries will lose their comparative advantage. This could be a problem for “late industrializers” (153).

Globalization has not produced the benefits it promises because the theories about globalization are wrong.

Economists are responsible for these misconceptions.[1] Economists have made several mistakes:

Economists have long ignored politics. They “think of national borders as a hindrance” and “deride the nation-state [as] the source of the transaction costs” that inhibit free market operations (17). But ignoring politics has been a mistake. First of all, people are deeply patriotic and they resist attempts to “transcend national sovereignty” (64). Secondly, initiatives that benefit the global community—such as freer trade—often run counter to national interests.[2] Policies should account for this and economists need to incorporate political economy into their models.

Economists “often forget . . . that economics is . . . a highly context-specific discipline” (114-5). In public debates, economists have been “overconfident” and glossed over “real-world complications and nuances” (118, 123). However, “there is virtually no question in economics to which ‘it depends’ is not an appropriate answer” (115). Choosing the right model for a situation is an “art” and a “craft” to which the discipline has devoted little attention (146). In an upper-level economic class, “a direct, unqualified assertion about the benefits of free trade [is] transformed into a statement adorned by all kinds of ifs and buts” (120).[3] Economists need to be upfront about the limits of their models.

Economists have not advocated for policies that would compensate those hurt by trade agreements. They have been “dismissive of the distributional consequences of trade agreements—consequences that their own models predicted so well” (114). Again, economists failed to account for political economy:

“Before a new policy—say a trade agreement—is adopted, beneficiaries have the incentive to promise compensation. Once the policy is adopted, they have little interest to carry out the compensation they promised—either because reversal is costly all around or because underlying balance of power shifts toward them.” (206)

The result is that, in the U.S., adjustment assistance programs have fallen by the wayside. Promises to compensate those hurt by trade agreements “have very little credibility today” and “the time for compensation has come and gone” (206).

The backlash against globalization should not be surprising, and economists bear some responsibility for it.

Good global governance respects national sovereignty. The international community will need to cooperate in order to address twenty-first century challenges like climate change. Successful initiatives will balance international cooperation with respect for national autonomy. Rodrik proposes seven guiding principles:

“Markets must be deeply embedded in systems of governance” (222). That is, governments should take an active role in regulating markets.

“Democratic governance and political communities are organized largely within nation-states, and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future” (223).

“There is no ‘one way’ to prosperity” (223).

“Countries have the right to protect their own regulations and institutions” (224).

“Countries do not have the right to impose their institutions on others” (224).

“The purpose of international economic arrangements must be to lay down the traffic rules for managing the interface among national institutions” (225). International regulations should “help vehicles of different size and shape and traveling at varying speeds navigate around each other, rather than impose an identical car or a uniform speed limit on all” (225).

“Nondemocratic countries cannot count on the same rights and privileges in the international economic order as democracies” (225). It is fair for countries to restrict trade with those that do not share their values (for example, countries that permit child labor or have inadequate environmental protections). Trade provides a natural incentive to liberalize.

Instead of blindly pursuing free trade, international arrangements should seek to foster fair trade.

Globalization has not delivered the widespread benefits its “cheerleaders” promised (3). The conventional wisdom about globalization was wrong. Economists encouraged these misconceptions by oversimplifying models during public debates and by failing to incorporate political economy into their models. Future globalization initiatives should balance international cooperation with respect for national sovereignty. Good globalization respects national autonomy.

Notes

[1] “Are economists responsible for Donald Trump’s shocking victory in the US presidential election? . . . [E]ven if they may not have caused (or stopped) Trump, one thing is certain: economists would have had a greater—and much more positive—impact on the public debate had they stuck closer to their discipline’s teaching, instead of siding with globalization’s cheerleaders” (i).

[2] “It is impossible to have hyperglobalization, democracy, and national sovereignty all at once; we can have at most two out of three” (5).

[3] Rodrik also argues that mercantilism may be a valid alternative to the classic comparative advantage theory of trade.

Globalize Gradually

Globalization and Its Discontents by Joseph Stiglitz vs. In Defense of Globalization by Jagdish Bhagwati

Countries should globalize gradually. Trade and market liberalization are fundamental drivers of economic growth. Liberalizing too rapidly, however, can be destabilizing—as the East Asian Crisis and Russia’s transition to a market economy show. The solution is a “gradualist” approach: slowly developing the institutions of an open economy. Despite the contrasting titles of their books, Stiglitz and Bhagwati agree that globalization can be good if pursued prudently.

Trade liberalization leads to growth. The empirical evidence “against an inward-looking . . . trade strategy is really quite overwhelming” (Bhagwati 61). The most comprehensive research on the subject comes from the OECD and NBER—two nonpartisan organizations who, in the 1960s and 1970s, published exhaustive studies of over a dozen developing nations (India, Brazil, Mexico, and more). Douglas Irwin’s case study of the McKinley tariff protection is another seminal work. The benefits of trade are well-established in economics. Articulating the theories is beyond the scope of this paper, but suffice it to say that “the most counterintuitive but true proposition in economics has to be that one can specialize and do better” (Bhagwati 61).

Rapid liberalization, however, can be destabilizing. At a minimum, “very rapid and large-scale trade liberalization” displaces “workers in import-competing industries” (Bhagwati 255). In the worst-case scenario, “hasty and imprudent financial liberalization” leads to crises and recessions (Bhagwati 199). During the East Asian Crisis of 1998, the “lack of banking and financial regulation[s]” enabled “panic-fueled outflows of capital” (Bhagwati 203, 200). The East Asian countries had exposed themselves to foreign capital flows before “their institutional practices had . . . been suitably modified for transition” (Bhagwati 203). Similarly, in Russia, “excessively rapid reforms” (Bhagwati 32)—“shock therapy”—precipitated the country’s recession in 1998.

Building the institutions of an open economy takes time. Developing nations usually lack the adjustment programs—such as unemployment insurance—that can help workers displaced by trade. On a grander scale, liberalization is more than simple deregulation; it requires “the establishment of the institutions that underlay a market economy” (Stiglitz 139). This “transformation of . . . social and political structures” takes time (Stiglitz 135). History shows successful countries have all liberalized gradually. China, by adopting a “gradualist approach” (Stiglitz 183), “averted” the East Asian Crisis and grew to become the world’s second largest economy (Stiglitz 126). Likewise, of the former Soviet Bloc countries, “Hungary, Slovenia, and Poland have shown that gradualist policies lead to less pain in the short run, greater social and political stability, and faster growth in the long [run]” (Stiglitz 188).

Trade liberalization drives economic growth, but, as the East Asian Crisis and the experience of Russia show, rapid liberalization can be destabilizing. “Great economists in the past”—from Adam Smith to John Maynard Keynes—“have uniformly been against shock therapy” (Bhagwati 253-4) Because the institutions of an open economy take time to develop, countries should globalize gradually.

Globalization and Its Discontents by Joseph E. Stiglitz

Book Summary

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) needs reform. The IMF has failed to both develop poor countries and provide stability during financial crises. The problem is the IMF’s institutional culture: the organization adheres to free market theories with “ideological fervor” and serves the financial community more than its client countries (Stiglitz 13). IMF practices have fostered the popular (and populist) discontent with globalization.

IMF policies are harmful. Stiglitz shows this through a careful country-by-country analysis of IMF initiatives since the 1980s. Three clear examples:

Argentina, despite studiously following IMF strategies, “has [had] double-digit unemployment for years” (27).

Kenya experienced “fourteen banking failures . . . in 1993 and 1994 alone” (32).

Russia’s transition from communism to capitalism was facilitated by the IMF. Before the

transition, Russia had a 2% poverty rate; “by late 1998, that number had soared to

23.8%” (153).

Countries that “explicitly reject” IMF strategies are often more successful (126). Two clear examples:

Malaysia did so during the East Asian Crisis of 1997 and experienced the shortest downturn.

China “averted” the crisis altogether by following policies “directly opposite” those advocated by the IMF (126).

The IMF has admitted mistakes in several of the situations above.

IMF policies rest upon debatable economic theory. The IMF’s standard policy prescription is the Washington Consensus: “fiscal austerity, privatization, and market liberalization” (53). Fiscal austerity—despite being an appropriate response to hyperinflation—is disastrous during a recession. Privatization and market liberalization are better policies, but the IMF pursues them with “excessive zeal” (64)—i.e., too rapidly. “Shock therapy” privatization leads to corruption and monopolies (141). Similarly, brisk trade liberalization squashes budding domestic firms, and financial market liberalization is destabilizing without a proper regulatory environment in place. (Stiglitz recommends a “gradualist” approach instead (141).)

The IMF reflects the “perspectives and ideology of the financial community” (207). Indeed, many of the IMF’s “key personnel” are alumni of or later recruited by financial firms (207). In addition to “market fundamentalism” (35), the IMF has embraced “Wall Street culture.” The Fund has a “prevailing culture of secrecy” and bullies client countries during loan negotiations (51). (Conditionality terms, for example, require a country to implement IMF political policies in order to receive funds.) In the end, many IMF initiatives—notably financial market liberalization and “bail-ins”—have benefited the financial community more than developing nations.

No wonder opponents of globalization see conspiracy. IMF initiatives since the 1980s have been harmful because they rest upon weak—or at least debatable—economic theory. The Fund has allowed the global financial community to overly influence its decision-making. The IMF needs reform.

Insights from Paul Graham’s Essays

When I was in college, my economics advisor suggested that I write summaries of all of the nonfiction books I was reading in order to help the information sink in. I was doing an independent reading project with him and the summaries I wrote became the first posts on this blog.

Now that I'm a product manager, I'm doing a lot of independent reading again. It's not that I don't read regularly — I do. Reading is one of my favorite hobbies and I tend to read 1-2 books a week. But most of the books I'm reading now are nonfiction books I'm trying to learn from in order to be better at my job. I don't want to forget the information I've read, and so I figured I'd revive the practice of summarizing my independent reading here.

First up: Paul Graham's essays.

Paul Graham runs the start-up accelerator Y Combinator, which counts Dropbox, Airbnb and Justin.tv among its early-stage investments. He's also the former founder of ecommerce start-up Viaweb, which was acquired by Yahoo! in 1998 and may have been the first web application.

Graham's essays run the gamut from start-ups to public policy to programming languages to Silicon Valley culture to fundraising. Most of his essays are from the early-to-mid 2000s, so some of the specific technology trends he writes about can feel a bit dated now. But by and large his writing is evergreen, and his essays contain a surprising amount of career and life advice (and, let's face it: if you're working at a start-up, your career kind of is your life).

Here were my biggest takeaways:

“If you’re not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you’ve launched too late.” Actually, Reid Hoffman, not Paul Graham, said that. But while Hoffman coined the quote, Graham gives similar advice over and over again.

If you release early, then you can start learning from your users. On the other hand, if you launch only after you’ve executed according to a grand business plan, then you'll find out too late that many of your original ideas were flawed.Start-ups allow you to compress your working life into a few years. In a start-up, you work insane hours. But if you exit successfully after a few years, then you're set for life.

Of course, to try this, you need a fairly high tolerance for risk. Typically, only 1 in 10 start-ups succeed. But there's no better time to try than when you're in your 20s and don't have a family to support (or other life commitments).

Graham puts the turning point for most start-ups at "ramen profitability" — when the company is making enough money to pay the founders' meager living costs.Maker’s schedule, manager’s schedule. Makers need long, uninterrupted blocks of time to do creative work. A meeting in the middle of the afternoon can make the afternoon unproductive even if the meeting is just thirty minutes long.

Webapps allow you to release quickly, i.e., multiple times a day instead of every few months. Building Viacom as a webapp allowed the team to stay ahead of their competitors. Customers also loved calling about an issue and then seeing it fixed later that day.

(Side note on speed: Viacom was also built using LISP, a high-level and relatively obscure language. Graham writes how uncommon LISP was at the time — most software was written in C++ or Java. LISP's advantages as a programming language also helped Viacom outmaneuver their competitors.)Put developers in touch with users. At Viacom, Graham and other developers would take support calls from customers. Most companies — even small, 10-15 person companies — don't do this and instead protect their developers with a dedicated support team. But I like the idea: developers in touch with customers have better insight into their customers' needs.

Don’t die. The best way to succeed as a start-up is to simply not die. Stay scrappy.

Graham also has lots of advice for fundraising, if your start-up is at that stage.

Designing for Growth by Jeanne Liedtka and Tim Oglivie

Aside from a few well known graduate schools offering immersion education—notably Stanford's d.school and U. Toronto's Rotman School, there isn't a wide variety of readily available ways to gain a learning experience blending theory with technique.

That's exactly the design challenge taken on by Jeanne Liedtka, a professor at U. Virginia's Darden Graduate School of Business and Tim Ogilvie, CEO of the innovation strategy consultancy Peer Insight, in their new book Designing for Growth: A Design Thinking Took Kit for Managers.

Pretty thorough review of Liedtka and Oglivie's book over on American Express's Open Forum.

Crush It! by Gary Vaynerchuk—Vook Edition

I just came across an advertisement for Gary Vaynerchuk's Crush It! The book looks fantastic—it's definitely going on my to-read list—but even more impressive than the paper or ebook editions is this one from Vook:

Crush It! by Gary Vaynerchuk - Vook Edition

Head to the site to watch the trailer.

Vook is an innovative publishing start-up that produces, well, Vooks—books that blend video with text. From what I gather, short videos are interwoven into the body of the book. This seems ideal for Crush It!, because Vaynerchuk is such an engaging motivational speaker. Short YouTube clips of him at conferences can run alongside the text.

Other than that, Vaynerchuk's content—and the story of his rise to fame/fortune/success—seems similar to that of Tim Ferriss.

Three Month Summary

This course has exposed me to the burgeoning field of behavioral economics. Neoclassical economics may be the “study of resource allocation under scarcity,” but behavioral economics is a blend of economics and psychology—the study of how people actually make decisions. Neoclassical models necessarily make simplifying assumptions, and behavioral economics explains the glitches and phenomena that traditional theory excludes. Laboratory experiments in both psychology and economics departments have demonstrated that while the rational consumer is a useful construct, he is ultimately fictitious.

As Clay Shirky shows in Cognitive Surplus, and as Chris Anderson to a lesser degree demonstrates in Free, people often behave in ways that are not profit-maximizing. The traditional foil to neoclassical theory is the ultimatum game: responders will turn down free money if they believe they are receiving an unfair deal. And, as William Poundstone explains in Priceless, decision-making can be influenced by hormones, blood alcohol content, race, gender, and other human variables. Poundstone’s conclusions are not new; economists have been modeling these effects for decades.

What is new is the Internet. Never before has such a market existed, and never before has it been so easily to collect data and study social groups. The Internet is unique in several ways. Firstly, there is virtually no cost to starting an online business—there are zero barriers to entry and exit. Secondly, the Internet allows information to flow phenomenally fast, thereby eliminating information asymmetries. Likewise, it distorts geography and time: individuals across the globe can communicate in real-time, and a researcher can access decades-old news articles with a quick Google search. The Internet is a nearly perfectly competitive market. The prices of goods fall to little more than their costs of production and, at first glance, there seems to be little room for profit.

The Internet’s effect is similar to that of the Industrial Revolution. Today, companies centuries old are failing while start-ups are thriving. The Internet era demands new business models. Michael Porter’s cost-leadership strategy is no longer enough; firms will have to differentiate themselves by adding value for their customers. (One way to do this, Daniel Pink suggests, is by focusing on design and those creative, human touches that cannot be replicated by software.)

The Internet also promotes super-monetary economies. With a glut of entertainment options available, a consumer’s scarcest resources are his or her time and attention. When one’s material needs have been mostly satisfied, he moves up Maslov’s hierarchy of needs. People log onto the Internet to participate, to connect with like-minded individuals. They express themselves in art, writing, and video—they will create for free—in exchange only for an audience. Furthermore, as Clay Shirky points out, people will often take on challenging tasks simply in order to master them or to feel autonomous. On the Internet, success is measured not in dollar signs but in reputation, and the primary currency is that of attribution—giving credit where credit is due.

There are several implications for aspiring managers. Daniel Pink argues that Peter Drucker’s “knowledge worker” has been supplanted by the right- and left-brained “conceptual worker.” While this may be more prediction than perception, it is not unrealistic to suggest that tomorrow’s workers will have to communicate as much as they quantify. The physical workplace is less important than the worker himself; tomorrow’s organizations will be decentralized and office hierarchies will be more fluid. Social media will both unite offices and keep them in touch with the outside world. (For a guide to becoming the ultimate mobile warrior, read Timothy Ferriss’s 4-Hour Workweek; to become a social media expert, read anything by David Meerman Scott.) Finally, in a hyper-connected world, workers will be challenged simply to define their work, to sort out critical information from what is superfluous, and to stay focused. Workers should embrace iterative design theory: “nothing will ever be perfect,” writes David Meerman Scott, suggesting that companies should launch products as soon as possible and revise them later, with user feedback. Managers may need to teach their employees how to work as much as give them orders—a copy of David Allen’s Making It All Work should suffice.

Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (and How to Take Advantage of It) by William Poundstone

Sorry it's been so long, guys.

Priceless is a well-researched history of behavioral economics. Poundstone goes out of his way tell the stories of Sarah Lichenstein, Paul Slovic, S. S. Stevens and the other researchers who punched holes in neoclassical theory—and the result is a book that is thoroughly engaging.

Poundstone argues that prices are largely arbitrary. Just as people are relatively poor judges of absolute temperatures and weights but can easily estimate changes, so too do customers have little sense what goods should be worth. Instead, they judge whether prices are acceptable or not from environmental cues. Poundstone repeatedly demonstrates the power of anchoring: a high set price can pull subsequent estimations of value upward. For instance, amateur and professional real estate agents both conclude a house is worth more when the asking price is higher. Similarly, an overpriced watch in a designer goods store may never sell but serves to justify high prices on other products. And juries award more in damages when lawyers put arbitrarily high prices on their clients’ suffering. (Poundstone opens with an account of the landmark Liebeck v. McDonald’s case, in which a jury awarded Stella Liebeck $2.9 million in damages for the third-degree burns she received when spilled a cup of coffee on herself.)

Poundstone extrapolates the psychology of pricing to discounts in retail stores, menu layouts, and business negotiations. Some tips:

On a menu, center-justify items and list prices without dollar signs.

If an item is on sale, list the new price along with the original. The allure of a bargain may induce customers to spend more than they otherwise would. Instead of raising prices outright, “lower the discount” (232).

When negotiating a business deal with a man, examine his ring finger. If he is unmarried or has a ring finger close in length to his index finger, he is less likely to walk away from a deal.

In behavioral economics, the primary research tool is the classic ultimatum game. Poundstone describes several variations (competitions between genders or races; games played under the influence of oxytocin or alcohol) and their implications. Several experiments reveal biases subjects will not consciously admit to. Poundstone’s book is a powerful study of both pricing theory and modern society.

Free: The Future of a Radical Price by Chris Anderson

Free (Hyperion, 2009) continues the line of thought Chris Anderson developed in The Long Tail. As in his previous book, Anderson approaches digital markets from an economic perspective. While his language isn’t always crystal-clear (don’t read his book before bed), his reasoning is sound and informed.

In the digital era, technological advancement has driven the costs of the inputs of production—primarily bandwidth, processing power, and storage space—down to virtually zero. The challenges this presents are primarily psychological: we need to stop thinking in terms scarcity and start thinking in terms of abundance.

Like Clay Shirky does in Cognitive Surplus, Anderson analyzes nonmonetary economies (but with more statistical data). In the Internet era, the primary currencies are attention and reputation: since consumers have only limited time, producers must compete for it. Twenty-first century business models will focus not on simply delivering a service but adding value for customers (see also Daniel Pink’s A Whole New Mind).

This applies not only to media companies but to manufacturers as well, since even physical goods have some sort of branding or intellectual property associated with them. Anderson examines the Chinese fashion market—where piracy is rampant—to illustrate how designer knock-offs actually drive demand for premium goods. In case study after case study, Anderson proves that free products create markets where there were none.

In his last chapter (pages 251-254) and in various sidebars, Anderson lists over fifty businesses that make money by offering free services. Anderson used to offer a free copy of his book on his website, and any aspiring entrepreneur would do well to read through it. In sum, there are three main business models a company can follow:

Direct Cross-Subsidies: Higher-paying customers subsidize lower-paying ones. Think museum admissions: adults pay while children get in free.

The Three-Party Market: A third party subsidizes the cost of offering customers a product at reduced rates. This is the way the media industry operates: advertisers pay the costs of producing content that anyone can access.

Freemium: Some customers purchase a premium product while others try a basic version at no cost. This is the model most software—think QuickTime (bundled with OSX) versus QuickTime Pro ($29.99)—sells with.

FastCo interview with Marcus Buckingham, author of First, Break All the Rules

Every manager is different, but what they do differently you could sum up with that mantra I put in chapter two, "They don't try to put in what God left out; they try to draw out what God left in. That's hard enough."

Great interview over on Fast Company with author Marcus Buckingham, of First, Break All the Rules fame. I love his data-driven approach to analyzing business leadership.

Cognitive Surplus by Clay Shirky

Cognitive Surplus (Penguin Press, 2010) is a sequel of sorts to Shirky’s popular 2008 book Here Comes Everybody. Shirky writes on his website that he “stud[ies] the effects of the Internet on society,” and both titles examine group dynamics on websites like Wikipedia, MySpace, and Twitter. In Cognitive Surplus, Shirky argues for the potential of collaborative new media to organize people to have a positive impact on society, and he supports his theories with examples of charitable organizations, social justice initiatives, and open-source software. Shirky is a professor of new media and journalism at NYU, and, though his arguments lack empirical rigor, his case studies are persuasive.

Shirky argues that forty-hour workweeks and rising prosperity have given us a “cognitive surplus”—that is, excess free time we used to otherwise spend watching television (Chapter 1). Since the Internet has democratized to the tools of media production, passive consumers have switched into active participants.

Using landmark psychology studies and behavioral economics, Shirky builds the case that people will often create for nonmonetary reasons. To the editors of Wikipedia or the teenage girls behind Grobanites for Charity, more important than monetary compensation are shared values and engagement in a community. Shirky also points out that individuals will often take on challenging tasks in order to master them or feel autonomous. Shirky’s hopeful thesis, quite simply, is that the Internet fosters collaboration that can use our free time for social good.

Shirky analyzes how fans of the South Korean boy-band Dong Bang Shin Ki organized to overturn trade legislation; how Nisha Susan’s Facebook group, the Association of Pub-going, Loose and Forward Women, changed women’s rights in India; and how open-source software like Linux and Apache get produced. Most relevant to business readers is his last chapter, where he offers a set of guidelines for fostering digital collaboration:

Start small: “Projects that will work only if they grow large generally won’t grow large” (194).

Ask “Why?”: “Designers have to put themselves in the user’s position and take a skeptical look at what the user gets out of participating, especially when the motivation of the designers differs from that of the user” (195).

Behavior Follows Opportunity: “What matters is how [users] react to the opportunities you give them” (196).

Default to Social: “The careful use of defaults can shape how users behave . . . . By assuming that users would be happy to create something of value for each other, Delicious [a social bookmarking site] grew quickly” (197).

A Hundred Users Are Harder Than a Dozen and Harder Than a Thousand: “A small group where everyone knows everyone else can rely on personality to arrange its affairs, while a large group will have some kind of preexisting culture that new users adopt. In the transition between those two stages is where culture gets established” (198).

People Differ. More People Differ More: “In participatory systems, . . . the behaviors of the most active and least active members diverge sharply as the population grows . . . . [Developers] can take advantage of this divergence by offering different levels of involvement” (200).

Intimacy Doesn’t Scale: “Yahoo.com host millions of mailing lists, to which tens of millions of people subscribe, but people are either on a mailing list or they are not—the lines around the individual clusters are clearly drawn. . . . [The] allegiance [of those users] is to the local cluster of people on their mailing list” (201).

Support a Supportive Culture: The riders in an Amtrak quiet car are “willing to police the rules themselves, because they know that if an argument ensues, the conductor will appear and take over enforcement” (202).

The Faster You Learn, the Sooner You’ll Be Able to Adapt: “When . . . Flickr.com was experimenting most actively with new features, it sometimes upgraded its software every half hour . . . . Meetup.com . . . has its designers watch people trying to user their service every day, instead of having focus groups every six months. . . . [S]uccessful uses of cognitive surplus figure out how to change the opportunities on offer, rather than worrying about how to change the users” (203-204).

Success Causes More Problems Than Failure: “As a general rule, it is more important to try something new, and work on the problems as they arise, than to figure out a way to do something new without having any problems.”

Clarity is Violence: “Culture can’t be created by fiat. . . . [T]he task isn’t just to get something done, it’s to create an environment in which people want to do it. [Allow groups] to accrue more governance as they grow” (205).

Try Anything. Try Everything: It is impossible to predict what will be successful, so try everything and allow users to experiment (“the only group that can try everything is everybody” (207)).

The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More by Chris Anderson

In comparison to David Meerman Scott's Real-Time Marketing & PR, Anderson's The Long Tail offers a rather sophisticated economic analysis of how the Internet is changing business. Anderson focuses mostly on the media and entertainment industries (probably because of his background as editor-in-chief of Wired), but he does do a superb job of extending his analysis to traditional retail (by examining Amazon.com and eBay). Anderson's research is a bit outdated—most of his data comes from before 2006, when the first edition of his book was published—but his theories are still relevant five years later. In 2008 he published an expanded second edition with an additional chapter on "The Long Tail of Marketing."

Anderson argues that the Internet is lowering the traditional costs of retail. In the past, companies were forced to offer only "hits" that had mass appeal. The world of physical products is inherently limited and there are opportunity costs to carrying on product over another. A movie has to earn enough at the box office to justify giving it screen time; a television program has to attract enough of an audience justify its spot in prime-time; and a CD has to earn shelf space by selling more copies than a less-popular album.

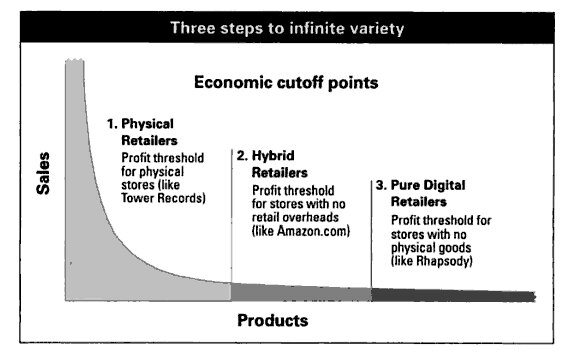

But, online, companies can offer infinite variety with little-to-no distribution costs. Services like Rhapsody.com or Netflix can offer thousands of mp3s or movie titles and deliver them to the consumer for the price of a broadband connection. Listing another product only costs (ever-cheaper) space on a server. Media companies can tap "the long tail" of the demand curve:

(The Long Tail 92)

The curve extends asymptotically: as Rhapsody added more mp3s to its library, it found that every single one of them sold.

Anderson's insight is that, in aggregate, these niche products can comprise a significant market. By examining companies from KitchenAid to LEGO—which have both physical and digital store fronts—he finds that online sales are becoming an increasingly large portion of revenue and profits.

(The Long Tail 132)

Because enthusiasts are often willing to pay more for niche products, the margins on them can be higher.

There are several implications of this long-tail shift. The first is that, as any microeconomist will tell you (and Anderson worked with Hal Varian, author of my microeconomics textbook), greater choice unambiguously increases welfare: consumers can find precisely the product they want at the price they are willing to pay. Secondly, consumers have more power than ever before because they can voice their opinions via blogs or product reviews ("twist[ing] some arms" with marketing “can only do so much" (232-233)). Ultimately, Anderson foresees mass culture fragmenting into tightly-knit, globe-spanning niches.

The challenge is to help consumers navigate this sea of variety. Long-tail businesses can crowdsource production and increase variety by aggregating the inventories of thousands of sellers (think Amazon Marketplace or eBay), but Anderson suggests that they can also play a (third) role as filters. With smart recommendation software (think Pandora's music genome project), retailers can lead consumers to new products they are likely to buy.

Finally, Anderson does an excellent job of placing the long-tail shift in historical context by examining the distribution innovations by Sears, Roebuck, and Co. and the cultural transformation caused by the home VCR.

Real-Time Marketing & PR by David Meerman Scott

With his 2008 bestseller The New Rules of Marketing & PR, David Meerman Scott redefined contemporary marketing thought. Scott explained how existing advertising strategies—expensive campaigns and interrupting television commercials—had been replaced by search engine optimization and websites that engage customers when they are actively seeking information about a product. In Real-Time Marketing & PR, Scott expands upon that line of thought by emphasizing the value of using new media tools to engage customers constantly and in real-time. Real-Time is more of a practical guide than a book of theory; Scott’s writing is characteristically informal, and his book is likely a compilation of posts from his popular blog Web Ink Now. Scott has a significant social media following and frequently speaks at corporate events.

In Real-Time Marketing & PR, Scott’s thesis comes (ironically) in the last chapter:

The explosion of online communication has led to a . . . loss of vendor control . . . in recent years. With email, social media, and alternative online media, consumers suddenly regained their collective voice in the marketplace. Faced with a vendor’s offer, consumers can once again scoff, rave, critique, or compare—and be heard far and wide. . . .

Far from making everything “new,” as many pundits insist, the Web has actually brought communication back full circle to where we were a century ago. What people respond to, and the way they make purchase decisions, really hasn’t changed at all. The difference is that word of mouth has regained its historic power.

The Web is just like a huge town square, with blogs, forums, and social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook serving as the pubs, private clubs, and community gathering places. People communicate online, meet new people, share ideas, and trade information. And yes, they sell products, too. (199)

Scott illustrates the power of social media through several poignant examples. In the most telling, Dave Carroll, a relatively-unknown rock musician from Canada, takes down United Airlines via a catchy song on YouTube. When baggage handlers mistreat his beloved Taylor guitar, Carroll seeks recompense by contacting the company through traditional channels. But after being shunted between customer service outlets for months, he writes the song “United Breaks Guitars” and posts it to YouTube. The video gains thousands of views within a day and over two million within a week; when CNN, Fox News, CBS, and even the BBC pick up the story, Carroll becomes a mass-media sensation. United continues to ignore the issue, but nimble companies like Calton Cases and Taylor Guitars reach out to Carroll to collaborate. While United suffers significant brand damage—their formal apology is only belated—both Taylor and Carlton see their sales skyrocket. “When luck turns your way, you can’t squander it,” says Bob Taylor of Taylor guitars. “This was a big branding leap.” Three months after his video, Carroll continues to speak to airlines and even the Senate about consumer rights. The lesson? Companies cannot afford to ignore the conversation occurring about them in real-time. [Read the full case study in the first chapter of Scott's book (pdf).]

“An immensely powerful competitive advantage flows to organizations” that are the first to break or act on a news story (35), and in the always-on new media world, even waiting “a whole hour” may be too long (36). Constantly monitoring Internet traffic sounds time-consuming, but Scott does offer some tips, including a detailed job description for a “chief real-time communications officer” (176) and some guidelines for freeing employees to use social media (and influence the conversation about their company in real-time) (162). Since the pace of business has increased, companies need to supplement their existing marketing programs with live communication strategies. In the end, “real-time is a mindset” (210).

Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors by Michael E. Porter

Michael Porter's Competitive Strategy was originally published in 1980 and has since become a classic of MBA programs and graduate economics courses in game theory. Porter’s book reads like a textbook—each chapter begins with a paragraph introduction but then follows with an outline of the relevant ideas, Porter is careful to exhaust all possibilities. Porter supports his theories with examples from the manufacturing sector. His micro case studies range from industries like construction machinery (Caterpillar and John Deere); to American car manufacturing (GM and Ford); “minicomputers” (Hewlett-Packard and Texas Instruments); and consumer watches (Timex and Swiss manufacturers). While Porter’s examples are a bit dated (he discusses “recent” legislation from before 1980), and while he admits in the updated introduction that “more service examples could be added” (xiii), he very thoroughly presents a framework for analyzing competition in any industry.

Porter posits the existence of five competitive forces within an industry:

Threat of Entry: “The threat of entry into an industry depends on the barriers to entry that are present, coupled with the reaction from existing competitors that the entrant can expect” (7).

Intensity of Rivalry among Existing Competitors: “Rivalry among existing competitors takes the familiar form of jockeying for position—using tactics like price competition, advertising battles, product introductions, and increased customer service or warranties” (17).

Pressure from Substitute Products: “All firms in an industry are competing, in a broad sense, with industries producing substitute products” (23); the threat of substitute products comes from outside the industry.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: “Buyers compete with the industry by forcing down prices, bargaining for higher quality or more services, and playing competitors against each other” (24).

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: “Suppliers can exert bargaining power over participants in an industry by threatening to raise prices or reduce the quality of purchased goods” (27).

In Porter’s view, competition plays out like a game of chess; he discusses “Competitive Warfare” in terms of “offensive or defensive moves” (89), and he frequently refers to the “battle” (189). Firms have three generic strategies that they can take:

Overall cost leadership: “Low cost relative to competitors becomes the theme running through the entire strategy” (35). This is a strong position to hold because it “protects the firm against all five competitive forces” (36) (“bargaining can only continue to erode profits until those of the next most efficient competitor are eliminated” (36)).

Differentiation: “Approaches to differentiating can take many forms: design or brand image . . . , technology . . . , features . . . , customer service . . . , dealer network . . . , or other dimensions” (37). Differentiation courts customers with “lower sensitivity to price” (37) and it “avoids the need for a low-cost position” (38).

Focus: “The final generic strategy is focusing on a particular buyer group, segment of the product line, or geographic market” (38). The firm following the focus strategy may strive for cost leadership, differentiation, or both, but only for “its narrow market target” (39).

Porter then offers a sophisticated framework for analyzing competitors and inferring their strategic standings (Chapters 3 and 7). Firms communicate their “pleasure or displeasure” as well as information about themselves through a variety of market signals (Chapter 4) (89). Porter discusses industry evolution and how the five competitive forces play out during different stages of “the product life cycle” (Chapter 8) (158). He follows with a detailed Part II that analyzes and recommends strategies to follow in fragmented, highly-competitive industries (Chapter 9); emerging industries in which a new product has just been introduced (Chapter 10); mature industries (Chapter 11); and declining industries (Chapter 12). He concludes by analyzing globalization in Chapter 13.

A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future by Daniel H. Pink

Is the MFA the new MBA?

Daniel H. Pink argues that today’s knowledge workers must augment their logical and analytical abilities with conceptual and creative skills. Pink identifies a “high-concept, high-touch” world and then delineates six key traits knowledge workers should cultivate. Pink supports his assertions with a flurry of statistics, factoids, and case studies: A Whole New Mind is more of a popular science book than a college textbook. But it is a quick, engaging read, and at the end of every chapter, Pink offers a “Portfolio” with advice for developing each of the six traits.

Delving into some soft psychology, Pink begins by defining L-directed and R-directed thinking:

Some people seem more comfortable with logical, sequential, computer-like reasoning. They tend to become lawyers, accountants, and engineers. Other people are more comfortable with holistic, intuitive, and nonlinear reasoning. They tend to become inventors, entertainers, and counselors . . . .

Call the first approach L-Directed Thinking. It is a form of thinking . . . that is characteristic of the left hemisphere of the brain—sequential, literal, functional, textual, and analytic. [It is] ascendant in the Information Age [and] exemplified by computer programmers . . . . Call the other approach R-Directed Thinking. It is a form of thinking . . . that is characteristic of the right hemisphere of the brain—simultaneous, metaphorical, aesthetic, contextual, and synthetic. [It is] underemphasized in the Information Age [and] exemplified by creators and caregivers . . . . (26)

Pink’s thesis is not that R-Directed thinking is superior to L-Directed, but that modern workers need to utilize both attitudes in order to thrive.

Pink argues that we have actually surpassed Drucker’s Information Age and entered the “Conceptual Age.” Pink identifies three forces at work: Asia, Automation, and Abundance. The first two are threats to today’s knowledge workers. Programmers in China and accountants in India can perform the same tasks as white-collar workers in the U.S., but for much less money (which allows them to earn a comparatively upper-middle class lifestyle overseas). Secondly, as computers become more sophisticated, L-Directed tasks will increasingly become automated. Consumers can go online to file their taxes, download divorce contracts, or obtain basic medical diagnoses; accountants, lawyers, and doctors who only fill out paperwork will become obsolete. And, finally, in our age of material abundance, products must do more than compete on the level of utility.

The typical person uses a toaster at most 15 minutes per day. The remaining 1,425 minutes of the day, the toaster is on display. In other words, 1 percent of the toaster’s time is devoted to utility, while 99 percent is devoted to significance. (80)

Products must appeal to customers’ aesthetic sensibilities in order to stand out.

Pink’s six traits are Design, Story, Empathy, Symphony, Play and Meaning. The first four refer to communication skills. Well-designed products are easy for humans to use (the 2004 Palm Beach ballots illustrate the perils of poor design). Stories weave disparate facts into a memorable whole; likewise, symphony is the ability to connect seemingly unrelated information and to think holistically. Finally, empathetic workers yield higher results (doctors who build relationships with their patients achieve higher rates of recovery, and this ability is more important than IQ, performance in medical school, hospital funding, or any other measure). Play and Meaning are ways to make the workplace more engaging.

On the whole, these are traits that cannot be replicated by computers and tend to become lost in long-distance telecommunication. These six senses add a human component to a service. Pink predicts that they will still be in demand in the immediate future.

The Definitive Drucker by Elizabeth Haas Edersheim

Peter Drucker is a business legend. He has contributed more to management theory than any other thinker, and he has inspired, mentored, and consulted with the CEOs of the world’s most successful companies. In 2005, at the age of 94, he invited Elizabeth Haas Edersheim to have unprecedented access to his person. For sixteen months, and for four to eight hours every day, Edersheim interviewed Drucker with the ultimate goal of creating a biography of his ideas. The result is The Definitive Drucker, which is both a primer of Drucker’s main ideas and a catalogue of personal quotes and wisdom. Edersheim supports Drucker’s theories with case studies and interviews (surprisingly in-depth), and she directs the book at “tomorrow’s executives” (every chapter heading is a question to provoke self-analysis and reflection).

Drucker coined the term “knowledge worker.” He is responsible for identifying the shift in the late 1980s from an industrial, manufacturing-oriented business landscape to a modern “Lego World” in which (1) information flies at hyperspeed; (2) companies have never-before-seen geographic reach; (3) customers defy demographic assumptions; (4) customers have increasing control of companies; (5) and the boundaries within and between companies are blurry and fluid.

Drucker repeatedly emphasized the value of knowing and connecting with customers. Companies need to continually ask themselves: Who are my customers, and what are their needs? The relationship between customer and company is increasingly complex, and Edersheim’s case study of Proctor & Gamble reveals that the company became successful only after focusing not on retailers (who valued simple product lines and timely delivery) but on consumers (whose needs were personal).

Drucker’s prescription for innovation echoes (or, rather, inspired) Timothy Ferriss. Drucker’s advice is to be aggressive where you lead but abandon profitable ventures. Edersheim offers the example of General Electric, which began as an industrial manufacturer but is increasingly involved in financial services and media. Innovators do more than tweak existing products: like Steve Jobs and Apple, they anticipate demands and create new markets.

Drucker’s most lasting contribution is his insight into managing and retaining knowledge workers. Because knowledge is intangible and fluid, employees who feel unfulfilled can easily take their skills to another company. Workers who are invested in and engaged in their work are more productive (organizations like Electrolux use online message boards to allow employees to “bid” for projects). It also helps if employees feel like they are part of a special team (Bob Taylor demonstrated the power of this culture at the famous the Palo Alto Research Center, where the modern personal computer was born). Drucker and Edersheim believe that the companies of tomorrow will be flat and decentralized. Management’s role will be to coordinate and unite disparate teams.

The 4-Hour Workweek by Timothy Ferriss

The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich is primarily a lifestyle guide. Ferriss may minutely detail how to automate revenue streams—he flowcharts the process and recommends specific companies to contact—but primarily he teaches an attitude that could be described as a mix of confidence and entitlement. This is how he recommends a “NR” or “New Rich” respond to a difficult customer:

Customer: What the &#@$? I ordered two cases and they arrived two days late?

Any NR—in this case, me: I will kill you. Be afraid, be very afraid.

(I have also seen Ferriss interviewed by Neil Strauss, author of The Game: Undercover in the Secret Society of Pick-up Artists. The attitude Ferriss recommends for the “NR” resembles Strauss’s vision of the Pick-up Artist (“PUA”). The 4-Hour Workweek applies Game social dynamics to office life.) Ferriss will recommend getting away with whatever you can—“What gets measured gets managed,” he says, quoting Peter Drucker—and working not efficiently but effectively.

In other words, work smarter. If “80% of the outputs come from 20% of the inputs” (Pareto’s famous Law), it is neither necessary nor ideal to spend resources getting outputs to 100%. One’s goal should be simply to tip the 80/20 ratio as high possible. If 90% of sales come from interactions with 10% of customers, then time is being used effectively. Ferriss advocates aggressive prioritization: “Focus on the important few [tasks] and ignore the rest.” He never reads the news.

Ferriss also explains how to start up a quick online retail business. He walks the reader through conceiving a product, testing it before production, advertising on the web and in print, and finally setting up automatic customer service and shipping procedures. Ferriss went through the process with his company, BrainQUICKEN, LLC, and he is able to recommend specific services and websites.

Ferriss is this thorough throughout his entire book. At times he may champion the free market to an almost radical extent—are there be ethical considerations in using Indian data miners to read email?—but his advice is specific enough to be applied by entrepreneurs and office dwellers alike (I plan to recommend it to Richard Nash, my mentor and the CEO of start-up Cursor and Red Lemonade). Ferriss’s aims to streamline personal and professional life, and he is right to point out that in a information-era economy, the most important resources are time and mobility.

Making It All Work by David Allen

David Allen could rightfully be called a personal productivity guru. His 2002 bestseller Getting Things Done inaugurated a movement that spread amongst writers, bloggers, and techies. Luminaries brag about being “GTD blackbelts.” Allen reports that each day fifty new blog posts are written about GTD, and there has been a raft of software tools developed (and marketed) to help users implement his process.

In Allen’s world, mastering workflow allows the individual to achieve a zen-like state of focus. Allen theorizes that the mind operates like computer RAM and will freeze up if it has too many open loops running at once. The solution, though, is not to decrease your commitments but rather to capture and sort them all. If your tasks are organized in a system you can trust to remind you of them—well, then you can stop thinking about everything you need to do and just do it.

Allen suggests that his process should be applied both in the office and at home. (Thus the subtitle, Winning at the Game of Work and the Business of Life.) The only way to fully de-stress is to capture all of your open loops.

Making It All Work teaches the reader a thinking process without worrying about the specific tools he uses. Allen’s solution is not the latest tool or gadget hyped to “boost productivity,” but rather a fundamental way to grapple with the variety of inputs in a knowledge-era economy.

The Processing Flowchart

How to get information out of your head and into a GTD system:

Capture—Write down everything on your mind, regardless of whether it’s a project, a to-do, a personal goal such as “get fit,” or something large and ambiguous like “Mom."

Clarify—Is it actionable? If so, ask yourself:

What’s the desired outcome?

What’s the next action?

Organize—Sort the action depending upon what it is:

Actions, if they don’t have specific due dates, go into context-sorted lists. If they do have specific due dates or you don’t need to worry about them until certain dates, write them down on your calendar.

Outcomes are larger goals. Keep track of them on lists sorted by horizon.

Incubating items are items you’re not sure what to do with yet. Write them on a Someday/Maybe list—to be reviewed weekly—or write them on your calendar.

Support or reference material goes into project-specific, labeled files folders or notebooks. For general thoughts, keep a journal.

Reflect—Review all of your projects weekly. Information changes over time. Items that were important before may no longer be priorities, or you may need to take different next steps to keep your projects moving. If you don’t review your lists, you won’t keep them current and you won’t trust your system. And, as David Allen says, “you can only feel good about what you’re not doing when you know what you’re not doing.” Reviewing gives you a sense of perspective.

Engage—With your lists you can objectively evaluate all of the possible next actions you can take. To remain productive, choose actions that most align with your values (Strategy) and that you can complete with the time, energy, and materials you have available (Limiting Factors).

Organizing on the Road Map (p. 136)

Incorporating All of the Engagement Factors (p. 179)