4 Ways the Web is Changing Communications

The web is changing how we organize information in four ways:

Taxonomies (think the Dewey Decimal System or biological classification) used to be necessary to organize information, but the web recognizes that categories are often fluid. Would my hypertext novella be found in the nonfiction, new media, prose or poetry section of a bookstore? The answer is neither and all four—it depends on who is looking for the book. With hyperlinks and tags, the web's architecture is primarily relational.

We rarely enter websites via their splash pages and instead access the page we want via Google, Bing, or another search engine. Even though technology allows news to break faster and memes to spread virally, old information is not so much forgotten as pushed to the fringes. For instance, Google "Ryan Gosling" and three of the top six hits will be images from The Notebook, even though the movie is seven years old and Gosling has starred in a movie every year since (including 2010's Blue Valentine, which won two awards and was nominated for seventeen more). Since old information can be accessed as easily as new, the web is inherently nonlinear.

With a blockbuster movie, a prime-time television show, or even a print book, the dialogue is one-way—from artist to audience. But the web has given consumers a voice and it rewards them for using it. If web content does not facilitate audience participation, surfers will take their attention elsewhere. The web is by nature interactive.

Literary writing is largely absent from the web because designers have not yet found ways to humanistically display longer works. The scroll bar on the side of a browser window actually represents a technological regression (think Egyptian papyrus scrolls). Longer documents, unless intuitively organized, lose all the advantages of print books (the abilities to instantly jump from beginning to end and to see how far you have progressed in the text). Because screen reading can be somewhat uncomfortable, web writing tends to be digestible in shorter chunks (e.g., the length of a blog post).

For my creative writing senior project, I'm writing a prose-poetry hypertext novella—a book-length work organized as a website. My novella tries to takes advantage of the above properties. It's partly an homage to my pre-digital childhood and partly a collage of memories (our present encompasses our past). Think of it as a fictional Wikipedia or a digital choose-your-own-adventure—it's an experiment in nonlinear storytelling.

I'm hoping these guys will publish it.

The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More by Chris Anderson

In comparison to David Meerman Scott's Real-Time Marketing & PR, Anderson's The Long Tail offers a rather sophisticated economic analysis of how the Internet is changing business. Anderson focuses mostly on the media and entertainment industries (probably because of his background as editor-in-chief of Wired), but he does do a superb job of extending his analysis to traditional retail (by examining Amazon.com and eBay). Anderson's research is a bit outdated—most of his data comes from before 2006, when the first edition of his book was published—but his theories are still relevant five years later. In 2008 he published an expanded second edition with an additional chapter on "The Long Tail of Marketing."

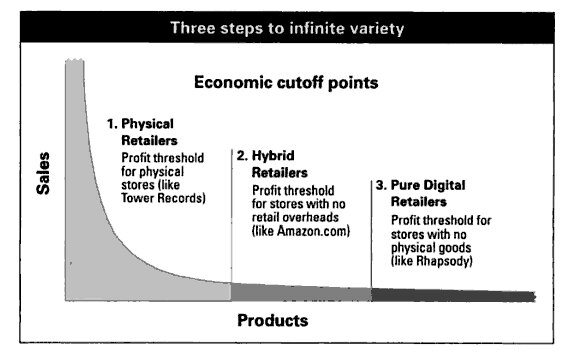

Anderson argues that the Internet is lowering the traditional costs of retail. In the past, companies were forced to offer only "hits" that had mass appeal. The world of physical products is inherently limited and there are opportunity costs to carrying on product over another. A movie has to earn enough at the box office to justify giving it screen time; a television program has to attract enough of an audience justify its spot in prime-time; and a CD has to earn shelf space by selling more copies than a less-popular album.

But, online, companies can offer infinite variety with little-to-no distribution costs. Services like Rhapsody.com or Netflix can offer thousands of mp3s or movie titles and deliver them to the consumer for the price of a broadband connection. Listing another product only costs (ever-cheaper) space on a server. Media companies can tap "the long tail" of the demand curve:

(The Long Tail 92)

The curve extends asymptotically: as Rhapsody added more mp3s to its library, it found that every single one of them sold.

Anderson's insight is that, in aggregate, these niche products can comprise a significant market. By examining companies from KitchenAid to LEGO—which have both physical and digital store fronts—he finds that online sales are becoming an increasingly large portion of revenue and profits.

(The Long Tail 132)

Because enthusiasts are often willing to pay more for niche products, the margins on them can be higher.

There are several implications of this long-tail shift. The first is that, as any microeconomist will tell you (and Anderson worked with Hal Varian, author of my microeconomics textbook), greater choice unambiguously increases welfare: consumers can find precisely the product they want at the price they are willing to pay. Secondly, consumers have more power than ever before because they can voice their opinions via blogs or product reviews ("twist[ing] some arms" with marketing “can only do so much" (232-233)). Ultimately, Anderson foresees mass culture fragmenting into tightly-knit, globe-spanning niches.

The challenge is to help consumers navigate this sea of variety. Long-tail businesses can crowdsource production and increase variety by aggregating the inventories of thousands of sellers (think Amazon Marketplace or eBay), but Anderson suggests that they can also play a (third) role as filters. With smart recommendation software (think Pandora's music genome project), retailers can lead consumers to new products they are likely to buy.

Finally, Anderson does an excellent job of placing the long-tail shift in historical context by examining the distribution innovations by Sears, Roebuck, and Co. and the cultural transformation caused by the home VCR.

Real-Time Marketing & PR by David Meerman Scott

With his 2008 bestseller The New Rules of Marketing & PR, David Meerman Scott redefined contemporary marketing thought. Scott explained how existing advertising strategies—expensive campaigns and interrupting television commercials—had been replaced by search engine optimization and websites that engage customers when they are actively seeking information about a product. In Real-Time Marketing & PR, Scott expands upon that line of thought by emphasizing the value of using new media tools to engage customers constantly and in real-time. Real-Time is more of a practical guide than a book of theory; Scott’s writing is characteristically informal, and his book is likely a compilation of posts from his popular blog Web Ink Now. Scott has a significant social media following and frequently speaks at corporate events.

In Real-Time Marketing & PR, Scott’s thesis comes (ironically) in the last chapter:

The explosion of online communication has led to a . . . loss of vendor control . . . in recent years. With email, social media, and alternative online media, consumers suddenly regained their collective voice in the marketplace. Faced with a vendor’s offer, consumers can once again scoff, rave, critique, or compare—and be heard far and wide. . . .

Far from making everything “new,” as many pundits insist, the Web has actually brought communication back full circle to where we were a century ago. What people respond to, and the way they make purchase decisions, really hasn’t changed at all. The difference is that word of mouth has regained its historic power.

The Web is just like a huge town square, with blogs, forums, and social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook serving as the pubs, private clubs, and community gathering places. People communicate online, meet new people, share ideas, and trade information. And yes, they sell products, too. (199)

Scott illustrates the power of social media through several poignant examples. In the most telling, Dave Carroll, a relatively-unknown rock musician from Canada, takes down United Airlines via a catchy song on YouTube. When baggage handlers mistreat his beloved Taylor guitar, Carroll seeks recompense by contacting the company through traditional channels. But after being shunted between customer service outlets for months, he writes the song “United Breaks Guitars” and posts it to YouTube. The video gains thousands of views within a day and over two million within a week; when CNN, Fox News, CBS, and even the BBC pick up the story, Carroll becomes a mass-media sensation. United continues to ignore the issue, but nimble companies like Calton Cases and Taylor Guitars reach out to Carroll to collaborate. While United suffers significant brand damage—their formal apology is only belated—both Taylor and Carlton see their sales skyrocket. “When luck turns your way, you can’t squander it,” says Bob Taylor of Taylor guitars. “This was a big branding leap.” Three months after his video, Carroll continues to speak to airlines and even the Senate about consumer rights. The lesson? Companies cannot afford to ignore the conversation occurring about them in real-time. [Read the full case study in the first chapter of Scott's book (pdf).]

“An immensely powerful competitive advantage flows to organizations” that are the first to break or act on a news story (35), and in the always-on new media world, even waiting “a whole hour” may be too long (36). Constantly monitoring Internet traffic sounds time-consuming, but Scott does offer some tips, including a detailed job description for a “chief real-time communications officer” (176) and some guidelines for freeing employees to use social media (and influence the conversation about their company in real-time) (162). Since the pace of business has increased, companies need to supplement their existing marketing programs with live communication strategies. In the end, “real-time is a mindset” (210).

Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors by Michael E. Porter

Michael Porter's Competitive Strategy was originally published in 1980 and has since become a classic of MBA programs and graduate economics courses in game theory. Porter’s book reads like a textbook—each chapter begins with a paragraph introduction but then follows with an outline of the relevant ideas, Porter is careful to exhaust all possibilities. Porter supports his theories with examples from the manufacturing sector. His micro case studies range from industries like construction machinery (Caterpillar and John Deere); to American car manufacturing (GM and Ford); “minicomputers” (Hewlett-Packard and Texas Instruments); and consumer watches (Timex and Swiss manufacturers). While Porter’s examples are a bit dated (he discusses “recent” legislation from before 1980), and while he admits in the updated introduction that “more service examples could be added” (xiii), he very thoroughly presents a framework for analyzing competition in any industry.

Porter posits the existence of five competitive forces within an industry:

Threat of Entry: “The threat of entry into an industry depends on the barriers to entry that are present, coupled with the reaction from existing competitors that the entrant can expect” (7).

Intensity of Rivalry among Existing Competitors: “Rivalry among existing competitors takes the familiar form of jockeying for position—using tactics like price competition, advertising battles, product introductions, and increased customer service or warranties” (17).

Pressure from Substitute Products: “All firms in an industry are competing, in a broad sense, with industries producing substitute products” (23); the threat of substitute products comes from outside the industry.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: “Buyers compete with the industry by forcing down prices, bargaining for higher quality or more services, and playing competitors against each other” (24).

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: “Suppliers can exert bargaining power over participants in an industry by threatening to raise prices or reduce the quality of purchased goods” (27).

In Porter’s view, competition plays out like a game of chess; he discusses “Competitive Warfare” in terms of “offensive or defensive moves” (89), and he frequently refers to the “battle” (189). Firms have three generic strategies that they can take:

Overall cost leadership: “Low cost relative to competitors becomes the theme running through the entire strategy” (35). This is a strong position to hold because it “protects the firm against all five competitive forces” (36) (“bargaining can only continue to erode profits until those of the next most efficient competitor are eliminated” (36)).

Differentiation: “Approaches to differentiating can take many forms: design or brand image . . . , technology . . . , features . . . , customer service . . . , dealer network . . . , or other dimensions” (37). Differentiation courts customers with “lower sensitivity to price” (37) and it “avoids the need for a low-cost position” (38).

Focus: “The final generic strategy is focusing on a particular buyer group, segment of the product line, or geographic market” (38). The firm following the focus strategy may strive for cost leadership, differentiation, or both, but only for “its narrow market target” (39).

Porter then offers a sophisticated framework for analyzing competitors and inferring their strategic standings (Chapters 3 and 7). Firms communicate their “pleasure or displeasure” as well as information about themselves through a variety of market signals (Chapter 4) (89). Porter discusses industry evolution and how the five competitive forces play out during different stages of “the product life cycle” (Chapter 8) (158). He follows with a detailed Part II that analyzes and recommends strategies to follow in fragmented, highly-competitive industries (Chapter 9); emerging industries in which a new product has just been introduced (Chapter 10); mature industries (Chapter 11); and declining industries (Chapter 12). He concludes by analyzing globalization in Chapter 13.

A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future by Daniel H. Pink

Is the MFA the new MBA?

Daniel H. Pink argues that today’s knowledge workers must augment their logical and analytical abilities with conceptual and creative skills. Pink identifies a “high-concept, high-touch” world and then delineates six key traits knowledge workers should cultivate. Pink supports his assertions with a flurry of statistics, factoids, and case studies: A Whole New Mind is more of a popular science book than a college textbook. But it is a quick, engaging read, and at the end of every chapter, Pink offers a “Portfolio” with advice for developing each of the six traits.

Delving into some soft psychology, Pink begins by defining L-directed and R-directed thinking:

Some people seem more comfortable with logical, sequential, computer-like reasoning. They tend to become lawyers, accountants, and engineers. Other people are more comfortable with holistic, intuitive, and nonlinear reasoning. They tend to become inventors, entertainers, and counselors . . . .

Call the first approach L-Directed Thinking. It is a form of thinking . . . that is characteristic of the left hemisphere of the brain—sequential, literal, functional, textual, and analytic. [It is] ascendant in the Information Age [and] exemplified by computer programmers . . . . Call the other approach R-Directed Thinking. It is a form of thinking . . . that is characteristic of the right hemisphere of the brain—simultaneous, metaphorical, aesthetic, contextual, and synthetic. [It is] underemphasized in the Information Age [and] exemplified by creators and caregivers . . . . (26)

Pink’s thesis is not that R-Directed thinking is superior to L-Directed, but that modern workers need to utilize both attitudes in order to thrive.

Pink argues that we have actually surpassed Drucker’s Information Age and entered the “Conceptual Age.” Pink identifies three forces at work: Asia, Automation, and Abundance. The first two are threats to today’s knowledge workers. Programmers in China and accountants in India can perform the same tasks as white-collar workers in the U.S., but for much less money (which allows them to earn a comparatively upper-middle class lifestyle overseas). Secondly, as computers become more sophisticated, L-Directed tasks will increasingly become automated. Consumers can go online to file their taxes, download divorce contracts, or obtain basic medical diagnoses; accountants, lawyers, and doctors who only fill out paperwork will become obsolete. And, finally, in our age of material abundance, products must do more than compete on the level of utility.

The typical person uses a toaster at most 15 minutes per day. The remaining 1,425 minutes of the day, the toaster is on display. In other words, 1 percent of the toaster’s time is devoted to utility, while 99 percent is devoted to significance. (80)

Products must appeal to customers’ aesthetic sensibilities in order to stand out.

Pink’s six traits are Design, Story, Empathy, Symphony, Play and Meaning. The first four refer to communication skills. Well-designed products are easy for humans to use (the 2004 Palm Beach ballots illustrate the perils of poor design). Stories weave disparate facts into a memorable whole; likewise, symphony is the ability to connect seemingly unrelated information and to think holistically. Finally, empathetic workers yield higher results (doctors who build relationships with their patients achieve higher rates of recovery, and this ability is more important than IQ, performance in medical school, hospital funding, or any other measure). Play and Meaning are ways to make the workplace more engaging.

On the whole, these are traits that cannot be replicated by computers and tend to become lost in long-distance telecommunication. These six senses add a human component to a service. Pink predicts that they will still be in demand in the immediate future.

The Definitive Drucker by Elizabeth Haas Edersheim

Peter Drucker is a business legend. He has contributed more to management theory than any other thinker, and he has inspired, mentored, and consulted with the CEOs of the world’s most successful companies. In 2005, at the age of 94, he invited Elizabeth Haas Edersheim to have unprecedented access to his person. For sixteen months, and for four to eight hours every day, Edersheim interviewed Drucker with the ultimate goal of creating a biography of his ideas. The result is The Definitive Drucker, which is both a primer of Drucker’s main ideas and a catalogue of personal quotes and wisdom. Edersheim supports Drucker’s theories with case studies and interviews (surprisingly in-depth), and she directs the book at “tomorrow’s executives” (every chapter heading is a question to provoke self-analysis and reflection).

Drucker coined the term “knowledge worker.” He is responsible for identifying the shift in the late 1980s from an industrial, manufacturing-oriented business landscape to a modern “Lego World” in which (1) information flies at hyperspeed; (2) companies have never-before-seen geographic reach; (3) customers defy demographic assumptions; (4) customers have increasing control of companies; (5) and the boundaries within and between companies are blurry and fluid.

Drucker repeatedly emphasized the value of knowing and connecting with customers. Companies need to continually ask themselves: Who are my customers, and what are their needs? The relationship between customer and company is increasingly complex, and Edersheim’s case study of Proctor & Gamble reveals that the company became successful only after focusing not on retailers (who valued simple product lines and timely delivery) but on consumers (whose needs were personal).

Drucker’s prescription for innovation echoes (or, rather, inspired) Timothy Ferriss. Drucker’s advice is to be aggressive where you lead but abandon profitable ventures. Edersheim offers the example of General Electric, which began as an industrial manufacturer but is increasingly involved in financial services and media. Innovators do more than tweak existing products: like Steve Jobs and Apple, they anticipate demands and create new markets.

Drucker’s most lasting contribution is his insight into managing and retaining knowledge workers. Because knowledge is intangible and fluid, employees who feel unfulfilled can easily take their skills to another company. Workers who are invested in and engaged in their work are more productive (organizations like Electrolux use online message boards to allow employees to “bid” for projects). It also helps if employees feel like they are part of a special team (Bob Taylor demonstrated the power of this culture at the famous the Palo Alto Research Center, where the modern personal computer was born). Drucker and Edersheim believe that the companies of tomorrow will be flat and decentralized. Management’s role will be to coordinate and unite disparate teams.

The 4-Hour Workweek by Timothy Ferriss

The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich is primarily a lifestyle guide. Ferriss may minutely detail how to automate revenue streams—he flowcharts the process and recommends specific companies to contact—but primarily he teaches an attitude that could be described as a mix of confidence and entitlement. This is how he recommends a “NR” or “New Rich” respond to a difficult customer:

Customer: What the &#@$? I ordered two cases and they arrived two days late?

Any NR—in this case, me: I will kill you. Be afraid, be very afraid.

(I have also seen Ferriss interviewed by Neil Strauss, author of The Game: Undercover in the Secret Society of Pick-up Artists. The attitude Ferriss recommends for the “NR” resembles Strauss’s vision of the Pick-up Artist (“PUA”). The 4-Hour Workweek applies Game social dynamics to office life.) Ferriss will recommend getting away with whatever you can—“What gets measured gets managed,” he says, quoting Peter Drucker—and working not efficiently but effectively.

In other words, work smarter. If “80% of the outputs come from 20% of the inputs” (Pareto’s famous Law), it is neither necessary nor ideal to spend resources getting outputs to 100%. One’s goal should be simply to tip the 80/20 ratio as high possible. If 90% of sales come from interactions with 10% of customers, then time is being used effectively. Ferriss advocates aggressive prioritization: “Focus on the important few [tasks] and ignore the rest.” He never reads the news.

Ferriss also explains how to start up a quick online retail business. He walks the reader through conceiving a product, testing it before production, advertising on the web and in print, and finally setting up automatic customer service and shipping procedures. Ferriss went through the process with his company, BrainQUICKEN, LLC, and he is able to recommend specific services and websites.

Ferriss is this thorough throughout his entire book. At times he may champion the free market to an almost radical extent—are there be ethical considerations in using Indian data miners to read email?—but his advice is specific enough to be applied by entrepreneurs and office dwellers alike (I plan to recommend it to Richard Nash, my mentor and the CEO of start-up Cursor and Red Lemonade). Ferriss’s aims to streamline personal and professional life, and he is right to point out that in a information-era economy, the most important resources are time and mobility.

Making It All Work by David Allen

David Allen could rightfully be called a personal productivity guru. His 2002 bestseller Getting Things Done inaugurated a movement that spread amongst writers, bloggers, and techies. Luminaries brag about being “GTD blackbelts.” Allen reports that each day fifty new blog posts are written about GTD, and there has been a raft of software tools developed (and marketed) to help users implement his process.

In Allen’s world, mastering workflow allows the individual to achieve a zen-like state of focus. Allen theorizes that the mind operates like computer RAM and will freeze up if it has too many open loops running at once. The solution, though, is not to decrease your commitments but rather to capture and sort them all. If your tasks are organized in a system you can trust to remind you of them—well, then you can stop thinking about everything you need to do and just do it.

Allen suggests that his process should be applied both in the office and at home. (Thus the subtitle, Winning at the Game of Work and the Business of Life.) The only way to fully de-stress is to capture all of your open loops.

Making It All Work teaches the reader a thinking process without worrying about the specific tools he uses. Allen’s solution is not the latest tool or gadget hyped to “boost productivity,” but rather a fundamental way to grapple with the variety of inputs in a knowledge-era economy.

The Processing Flowchart

How to get information out of your head and into a GTD system:

Capture—Write down everything on your mind, regardless of whether it’s a project, a to-do, a personal goal such as “get fit,” or something large and ambiguous like “Mom."

Clarify—Is it actionable? If so, ask yourself:

What’s the desired outcome?

What’s the next action?

Organize—Sort the action depending upon what it is:

Actions, if they don’t have specific due dates, go into context-sorted lists. If they do have specific due dates or you don’t need to worry about them until certain dates, write them down on your calendar.

Outcomes are larger goals. Keep track of them on lists sorted by horizon.

Incubating items are items you’re not sure what to do with yet. Write them on a Someday/Maybe list—to be reviewed weekly—or write them on your calendar.

Support or reference material goes into project-specific, labeled files folders or notebooks. For general thoughts, keep a journal.

Reflect—Review all of your projects weekly. Information changes over time. Items that were important before may no longer be priorities, or you may need to take different next steps to keep your projects moving. If you don’t review your lists, you won’t keep them current and you won’t trust your system. And, as David Allen says, “you can only feel good about what you’re not doing when you know what you’re not doing.” Reviewing gives you a sense of perspective.

Engage—With your lists you can objectively evaluate all of the possible next actions you can take. To remain productive, choose actions that most align with your values (Strategy) and that you can complete with the time, energy, and materials you have available (Limiting Factors).

Organizing on the Road Map (p. 136)

Incorporating All of the Engagement Factors (p. 179)